On this page, we share information about environmental contributors to the obesity epidemic.

Obesity Prevalence & Health Harms

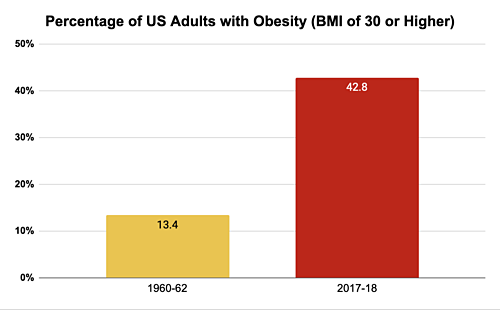

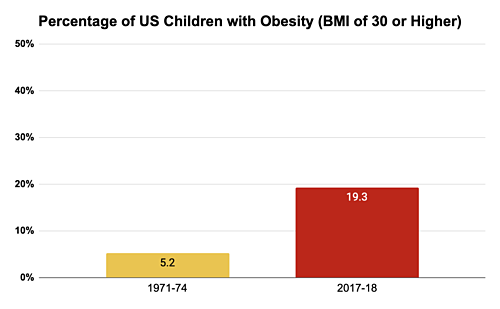

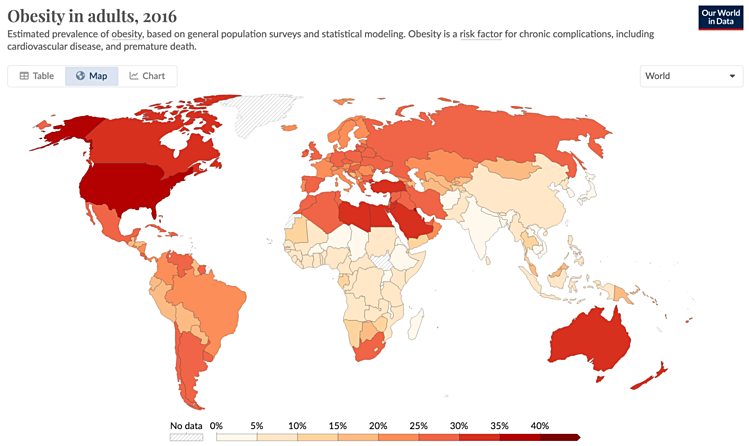

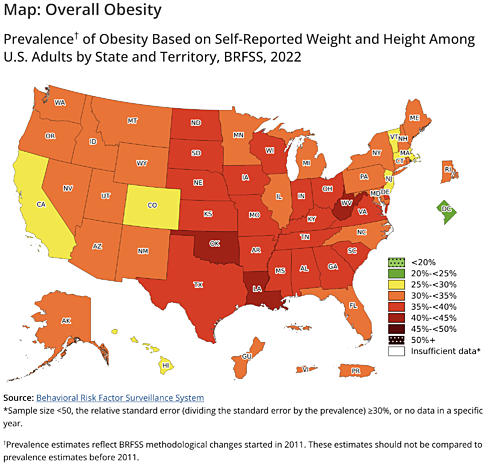

The rates of obesity in the United States reflect the global trend, with adult rates tripling since 1960. Currently over 40% of adults in the US have obesity.2 Obesity is indicated by a Body Mass Index (BMI) over 30. This measure is not always accurate in diagnosing obesity, but it is useful for public health screening.

Vulnerable Populations

Race and Ethnicity. Race and ethnicity influence the risk of obesity in the United States, with non-Hispanic Black adults and Hispanic adults experiencing the highest rates.6

Socioeconomic Status. Higher educational attainment has consistently been associated with a lower risk of obesity in white women. The association is less clear or consistent in men and non-white women.7 A similar pattern was found in an earlier report that included income: the prevalence of obesity in white, non-Hispanic females of all ages falls as family income rises. A similar association was found in white, non-Hispanic males aged 2-19, but the association is weak or even reversed in other groups.8 Thus there is some connection between income, educational attainment and risk of obesity, but it is not always consistent or conclusive. See CHE's Socioeconomic Environment webpage.

Research has found that low-income communities and communities of color have more limited access to healthful foods than other communities.9 The availability of healthy food options in a community often goes unnoticed in the background, but it can play a major role in people’s ability to eat healthy.10

Related Health Problems

People with obesity are at increased risk for a variety of health problems including: 11

- Type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD), including stroke

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- Arthritis

- Breathing problems

- Some cancers, especially of the esophagus, pancreas, colon and rectum, breast (after menopause), endometrium (lining of the uterus), kidney, thyroid, and gallbladder12

- Early puberty13

- Metabolic syndrome14

Environmental Contributors

Many factors are known to contribute to obesity, including chemical exposures, genetics, and other lifestyle factors, which we discuss here in turn. Increasing evidence shows that environmental exposures are a key driver of the increasing obesity trends.15

Obesogens and Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

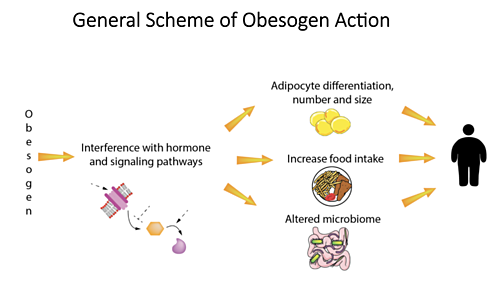

Chemicals that promote fat development are referred to as obesogens. According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), these exposures may not cause obesity directly, but are thought to increase an individual’s susceptibility for gaining weight, especially when exposure occurs during development, in infancy, and childhood.16

Many of the chemicals linked to obesity are part of a group called endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). EDCs are found in many everyday products, including plastics, detergents, flame retardants, food, toys, cosmetics, and pesticides. EDCs can alter the hormonal signals that control and guide much of our growth and development, the way our organs function, and our ability to fight disease.

Obesogenic EDCs are thought to stimulate adipogenesis (the process by which fat-storing cells develop and accumulate lipids). Adipogenesis is the key cellular process that leads to obesity.18 See our EDCs webpage for more details. See Diabetes and the Environment: Obesogens for more on the latest science around obesogens.

Here we highlight some chemicals to which large numbers of people are regularly exposed and which show strong evidence of acting as obesogens.19

|

Chemical |

Sources of Exposure |

Effects |

|

|

Combustion of fuels (diesel exhaust and biomass), as well as dust and other contaminants in air. |

Increases fat and inflammation in adolescents whose mothers were exposed. |

|

DDT / DDE |

DDT is a pesticide used to kill mosquitos; the body metabolizes DDT into DDE. |

Prenatal DDE is associated with increased infant growth. Animal and human studies show that DDT exposure can have obesogenic effects across generations.20 |

|

Dioxin and PCBs |

Dioxins are a product of incomplete combustion of organic material. PCBs were used in electronic transformers and capacitors. Dioxins and PCBs share similar chemistry and toxicity. They are persistent organic chemicals (POPs) that adversely affect humans and ecosystems long after they enter the environment. |

The direct obesogenic effects of these are not clear, but they have been shown to have inflammatory and metabolic effects. As a result, exposure in individuals with obesity could increase the likelihood of obesity-related metabolic and pathogenic effects. |

|

Chemicals applied to furniture, electronics, children’s clothing, foam, and insulation |

Increased rate of fat accumulation. |

|

|

Chemicals used to control weeds, insects, and other unwanted organisms; widely used in homes, schools, and businesses as well as in agriculture. |

Affect pancreatic function, cause abnormalities in lipid metabolism; promote obesity in response to increased dietary fat.21 |

|

|

PFAS |

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a class of more than 12,000 chemicals used in consumer products, industrial applications, and industrial firefighting foams. They are used in numerous consumer products such as food packaging, textiles, apparel, and non-stick cookware due to their stain, grease, and water resistance properties. |

PFAS exposure has been associated with alterations in multiple metabolic pathways. Exposure during key development periods is of particular concern because these are when cells become specialized to carry out distinct functions. |

|

Phthalates |

Phthalates are used widely in plastics, personal care products, fragrances, and other applications. Phthalates are not bound to plastic matrix and readily migrate into the environment. |

Studies have shown that at least some phthalates can induce adipogenesis. |

|

Tobacco smoke

|

First-hand and second-hand |

Smoking during pregnancy is strongly associated with the child's obesity. The extensive data this association provides strong proof of principle that environmental exposures can act as obesogens. |

|

Tributyltin (TBT) |

TBT is a biocide used as an antifouling agent on boats and nets, where it can contaminate seafood. It is also used as a fungicide on certain crops and is present as a contaminant in PVC plastics. |

TBT stimulates the differentiation of preadipocytes to adipoctytes and alters the brain feeding centers and liver lipogenesis (the metabolic formation of fat. |

Genetics and Epigenetic Programming

Genes play a role in obesity, causing some obesity disorders. However, having a specific gene variant, or set of variants, does not always mean that an individual will have obesity. Often with genetic components of diseases and disorders, an individual's environment—nutrition, activity, chemical exposures, sleep quality and so on—can either promote or inhibit the physical expression of genes.

The term "epigenetic programming" refers to mechanisms that can turn on or off genes or sections of chromosomes, changing their functioning. These changes are maintained as the cell replicates, and some research has shown that these changes can pass down to offspring. Changes in a fetus's genes by the mother's nutritional status during pregnancy are an example of epigenetic programming.22 Studies have identified multiple potential epigenetic mechanisms through which obesogenic chemicals could be contributing to obesity rates.23

For more information on genes and the environment, see our Gene-Environment Interactions webpage.

Other Factors

Diet and Exercise. An energy-dense diet, and especially foods high in fat and/or sugar,24 and lack of exercise and physical activity are strongly associated with obesity.25

Mother's Nutrition. Severe undernourishment (famine) by a pregnant woman has been associated with an increased risk of obesity in her child. When the mother is malnourished, the baby's genes involved with appetite regulators, pancreatic development, and obesity-associated genes can be affected, and these changes can last throughout the child's life.26

Maternal obesity also increases the risk of developing insulin resistance and has been associated with an increased risk of large gestational weight, fat accumulation, and type 2 diabetes in youth.27

Sleep and Stress. Evidence also links both sleep and stress to obesity.28 Research has found a strong association between individuals' working night shifts and increased body weight,29 with some evidence that poor sleep quality causes negative changes in metabolic, inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and antioxidant biomarkers.30 See our Psychosocial Environment page for more information on the effects of stress on health.

Prevention & Costs

Obesity is a complex issue that involves many aspects of society. To best prevent the development of obesity and to support those who have obesity, community responsibility must be addressed along with individual choices.

Community, governmental, and societal actions are needed to provide health-promoting food options, encourage physical activity, educate the public, and regulate the foods and chemicals that are associated with obesity.

Healthy Eating and Physical Activity

Modern society has reworked our systems of food and agriculture to make unhealthy food choices both more available and less expensive than healthier foods (see our Food and Agriculture Environment webpage). In addition, many neighborhoods, transportation systems, work and school environments, and recreational activities have likewise been altered or engineered to promote less physical activity as the norm in our lives31 (see our Built Environment webpage).

Governmental interest in addressing obesity is increasing, in part because of the huge economic and societal costs. Government actions include these:

- The World Health Organization's (WHO) lowering of sugar intake recommendations in 201532

- 2021 Healthy Food Service Guidelines from the CDC33

- The US Food and Drug Administration's 2016 changes to food labeling rules34

- New York City's efforts to curtail soda consumption35

- CDC's Physical Activity Guidelines, updated in 201836

- WHO's 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour37

Harvard’s School of Public Health outlines some policy suggestions that could help improve access to healthy food choices:

“Agriculture policy can focus on increased planting and buying of fresh fruits and vegetables. Revenue policy can focus on increasing taxes on unhealthy foods and subsidizing the cost of healthy choices. Zoning regulations can help bring supermarkets to low-income neighborhoods and limit fast-food restaurants in areas where there are already too many. And communication policy can restrict advertising to youth about unhealthy foods, or curb stealth marketing to youth through junk food product placements on prime-time television.”38

Reducing Obesogen Exposures

Policies that encourage healthy eating and physical activity seek to address energy intake and expenditure. However, this is not the whole picture. Obesogens change our metabolic processes, altering the balance between energy intake and energy expenditure, and increasing the overall prevalence of obesity. These hormone disrupting chemicals are found in consumer and industrial products like makeup, shampoos, soaps, plastics, cleaners, pesticides, and food packaging.

Reducing exposures can play a critical role in preventing obesity. Exposure occurs throughout the life course, starting even before conception. Research shows that the most sensitive time for obesogen action is in utero and early childhood.39 Therefore, we need government leadership to more thoroughly test and regulate potentially obesogenic chemicals.

Medical and social costs

Studies estimating costs of obesity-related illness in the United States show total costs in the billions. Studies in 2011 and 2021 estimate medical costs to be between $190 billion and $260 billion per year.40

These estimates do not include many indirect costs of obesity, such as work absences, decreased productivity while at work, and premature mortality and disability.41 An economic review of obesity discovered that obesity is among the most costly preventable diseases.42

Impacts of Weight Stigma

A recent BioMed Central article defined weight stigma as the "social rejection and devaluation that accrues to those who do not comply with prevailing social norms of adequate body weight and shape." Weight stigma is a form of discrimination based on a person's body weight.43

Individual behavior is often called into question regarding why an individual may have obesity or be overweight. These attitudes fail to take into account other contributing factors, such as environmental exposures outside of a person’s control, genetics, and social determinants of health.44

Studies have shown that even physicians show strong weight stigma in healthcare situations.45 This stigma impacts many aspects of psychological well-being and may also result in sub-optimal clinical outcomes for patients.46 This can have real impacts on both psychological and physical health.

For more of our work on this topic, click here to explore webinar recordings related to obesity and environmental health.

This page was last revised in March 2024 by CHE’s Science Writer Matt Lilley, with input from Sarah Howard of Healthy Environment and Endocrine Disruptor Strategies (HEEDS) and editing support from CHE Director Kristin Schafer.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.