-Dr. Shanna Swan, author of Count Down1

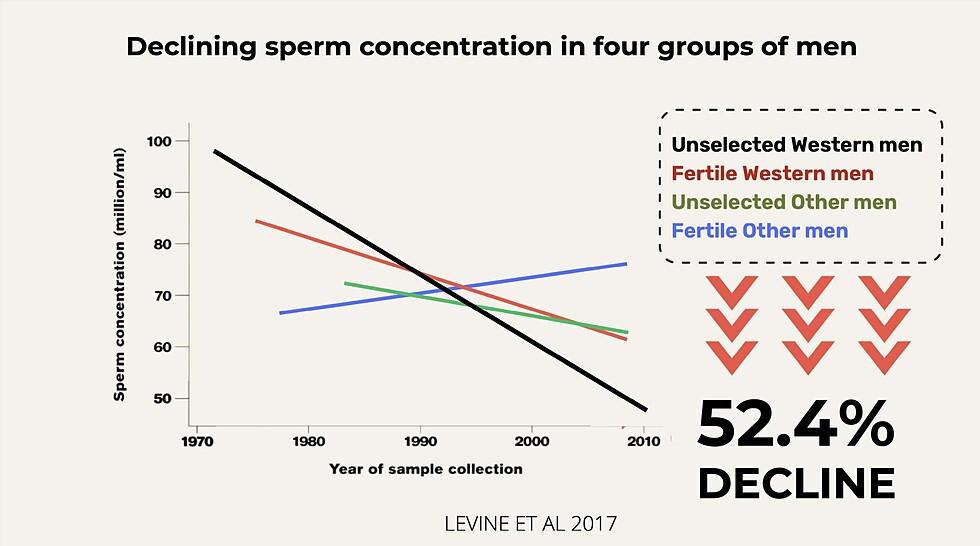

Approximately 9% of men and 13.1% of women of childbearing age have problems with infertility or impaired fecundity, according to the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.2 About 10% of couples in the US have difficulty getting pregnant.3 This includes younger couples; the problem is not fully attributable to age. It is also not attributed to increased diagnosis or reporting. Sperm counts have declined worldwide by 50-60% since the 1970s.4

External factors are linked to these disturbing trends, with evidence indicating that exposures to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), pesticides, heat, and lifestyle factors (such as diet and exercise) are contributors.6 Maternal and paternal exposures to EDCs and air pollution have been found to influence the genes that are linked to sex steroid hormones, which impact fertility and pregnancy.7

Studies have shown that fertility status can be a window into overall health. Increased infertility in a population could be a harbinger of future health impacts from environmental exposures.8 By amplifying fertility research, CHE is helping to promote investment in upstream disease prevention. By advocating for policies focused on prevention, we are working to ensure a sustainable and healthy future.

Environmental Toxicants and Fertility

Exposure to environmental toxicants is linked with various reproductive diseases and disorders, many of which harm fertility. Below we highlight some key categories of potential exposures.

|

Air Pollution |

Exposure to traffic-related air pollution has been consistently related to lower fecundity and fertility among women. |

|

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) |

A wide range of chemicals can disrupt the endocrine system, including phthalates, pesticides, flame retardants, and dioxins. EDCs are found in many everyday products, including plastics, detergents, flame retardants, food, toys, cosmetics, and pesticides. EDCs can alter the hormonal signals that control and guide much of our growth and development, the way our organs function, and our ability to fight disease. Current science provides evidence linking exposures to EDCs and many male reproductive health problems with increased risk of disease later in life.9 Data showing associations between EDCs and female infertility and miscarriage also continue to grow as more research is done.10 |

|

Phthalates |

Phthalates are one category of EDCs. Phthalates are used widely in plastics, personal care products, fragrances, and other applications. People are exposed to phthalates through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact. Exposures often come through consumer products and can also be occupational hazards. These compounds are quickly metabolized to more active compounds in several tissues. Studies indicated that the phthalate metabolites reach the ovary. Data shows mixtures of phthalate metabolites can directly impact follicle health, which is a vital part of a woman’s fertility.11 Phthalates also affect male reproductive development. Male reproductive outcomes from in utero exposure to phthalates has been referred to as “phthalate syndrome.”12 |

|

PFAS |

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a class of more than 12,000 chemicals used in consumer products, industrial applications, and industrial firefighting foams. They are used in numerous consumer products such as food packaging, textiles, apparel, and non-stick cookware due to their stain, grease, and water resistance properties. A recent study found that women with higher levels of PFAS in their blood had a 30-40% less chance of conceiving within a year of trying.13 |

Fertility and Epigenetics

Environmental exposures can change gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms. For example, worker bees and a queen bee are genetically identical. When a developing bee is fed royal jelly, an epigenetic modification is made to the reproductive genes and they turn on. The genes have not changed, but whether they are active or not has.

In humans, a hormone circulating in a mother’s bloodstream can affect the developing reproductive system of her fetus. When the hormone enters a cell, it binds a receptor that then binds with a specific stretch of DNA called a “hormone response element.” By binding, the gene is turned on (transcribed).

It is through this process that EDCs can alter gene function in pathways associated with infertility, obesity, cancer, and osteoporosis.14 In this way, a pregnant mother’s exposure to EDCs can impact the fertility of her offspring.

CHE's Work on Fertility

From Ali Carlson's How CHE Fertility Came into Being, and How It Helped Shape the Reproductive Health & Environmental Health Fields:

“CHE Fertility's collaborative work essentially defined the field of reproductive environmental health. Without CHE and the expertise of the pioneering researchers, health professionals and advocates that it attracted, the emergence of what is now a highly robust field would likely have taken years if not possibly decades more to develop.

"In short, CHE Fertility was at the center of launching an effective, multidisciplinary endeavor that bridged science with medicine, health advocacy, and policy that ultimately put reproductive environmental health on the map of priorities for scientists, health professionals, and concerned citizens alike.”

The pioneering actions that made CHE Fertility so successful included:

- Organizing a range of stakeholders around credible science, in particular establishing partnerships between federal agency leaders, advocates, scientists, and doctors

- Bringing heft and validity to the concerns raised by the science, signaling its importance to decision-makers in medicine, policy, and funding

- Propagating the logic and far greater efficiency of investing in upstream disease prevention as an important complement to the 96% of dollars invested in disease in the US going toward treatment

- Galvanizing a large choir of sophisticated messengers and catalysts who inform policy debates, influence research agendas and funding priorities, as well as clinical care

- Engaging a set of leading professional associations until they paid attention. Those societies upped the ante, becoming critical voices in health care sector and on Capitol Hill, with the steady assistance from CHE Fertility partners

- Providing an important platform for nurses, who became some of the most proactive and effective voices for improved understanding and practice

- Pressing for research agendas (and funding) to fill critical knowledge gaps

Also see CHE's publications related to reproductive health and fertility on our Resource Library page.

Vallombrosa Statement

Vallombrosa Consensus Statement on Environmental Contaminants and Human Fertility Compromise, 2005. CHE's Fertility/Early Pregnancy Compromise Work Group partnered with Linda C. Giudice, MD, PhD, to convene a small multidisciplinary group of experts at the Vallombrosa Retreat Center in Menlo Park, California. The group's goal was to assess what the science tells us about the contribution of environmental contaminants—specifically synthetic compounds and heavy metals—to human infertility and associated health conditions.

Women's Reproductive Health and the Environment Workshop

Meeting in January 2008, the Women’s Reproductive Health and the Environment Workshop fostered a collaboration of eminent and up-and-coming scientists specializing in women’s reproductive health. Organized by the CHE in partnership with the University of Florida and PRHE, this invitational workshop had three goals:

- Assess the key science linking environmental contaminant exposures to reproductive health outcomes currently being reported at ever greater rates in women and girls.

- Identify research directions that will fill current gaps in the scientific understanding in this field.

- Translate this information for a lay audience of journalists, policymakers, NGOs, community groups and others who can develop a strategy for prevention and intervention.

The workshop led to the publication of a peer-reviewed article that illustrated the role of EDCs in numerous human female reproductive disorders.15 In addition, the workshop led to the publication of a report for a non-scientific audience: Girl, Disrupted: Hormone Disruptors and Women's Reproductive Health and a summary brochure in two versions: a trifold brochure for a general audience: Hormone Disruptors and Women's Health: Reasons for Concern and an annotated version for researchers. These publications were used to lobby for increased federal funding for women's environmental health research.

Summit on Environmental Challenges to Reproductive Health and Fertility

In 2007, the Summit on Environmental Challenges to Reproductive Health and Fertility was convened at the Mission Bay Campus of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).The Summit was the product of a collaboration between the UCSF Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment (PRHE), the UCSF National Center of Excellence in Women's Health, and CHE. This conference was designed for clinical researchers and clinicians/health professionals, scientists; allied and public health professionals; policy makers, government; leaders from patient advocacy, women's health, community and worker health, environment, reproductive advocacy, and environmental justice; and environment/health funders. Participants exchanged the latest research around environmental contaminants and reproductive health, discussed how the science impacts public health, education, policy, and the health care system and explored mutual areas of collaboration among the diverse constituencies participating in the summit. Proceedings were published in 2008.16

Since that summit, CHE’s work has been intertwined with PRHE’s, and we continue to collaborate in many ways. We organized the Generation Chemical webinar series together in 2020, and in 2023 we've co-hosted a series of online events focused on healthy building materials and environmental justice, and several webinars focused on strengthening national chemicals policy.

To explore recent webinars, blogs and partner resources on infertiliy, see our Key Topics page.

This page was last revised in February 2024 by CHE’s Science Writer Matt Lilley, with input from Julia Varshavsky, PhD, MPH, and editing support from CHE Director Kristin Schafer.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.