Although it is traditionally understood as a disease arising from various combinations of diet, obesity, smoking, poor physical fitness, and family history, research also finds increased risk of CVD from a wide variety of environmental exposures.1

Types of Cardiovascular Disease

The term cardiovascular disease includes diseases involving the heart and circulatory system. Some of the most common forms of CVD include:

Coronary artery disease or CAD, also known as atherosclerotic heart disease, is the most common type of heart disease in the United States and can lead to heart attacks. The condition is caused by plaque buildup (atherosclerosis) in the lining of arteries that supply blood to the heart.

Heart attacks, also called myocardial infarctions, occur when blood flow to part of the heart muscle is insufficient, usually due to a blood clot or ruptured plaque. Coronary artery disease is the main cause of heart attacks; however, a severe spasm or sudden contraction of a coronary artery can also stop blood flow to the heart muscle.

High blood pressure, also called hypertension, is characterized by blood flowing through blood vessels at higher than normal pressures. About one in three US adults have high blood pressure.2

Low blood pressure, also called hypotension, can also be a symptom of cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure, heart attack and valve problems.

Cerebrovascular disease is most commonly caused by plaque buildup in arteries supplying blood to the brain. Strokes occur when blood does not flow properly to the brain, injuring brain tissue. This can result from a clot that blocks the flow of blood (called an ischemic stroke) or a rupture of a blood vessel in the brain, leading to bleeding (called a hemorrhagic stroke). Each year, 795,000 people in the US are estimated to suffer strokes, and roughly 130,000 will die of the event.3

Heart failure occurs when the heart is unable to pump a sufficient supply of oxygen-rich blood to the body. Due to weakening or stiffening of the heart muscle, heart failure can result from coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, or abnormalities of heart valves or muscle. About 5.8 million people in the United States have heart failure, and about half of those who develop heart failure will die within five years of diagnosis.4

Congenital heart defects are not included here but are discussed on our Birth Defects page.

Prevalence and Costs of Cardiovascular Disease

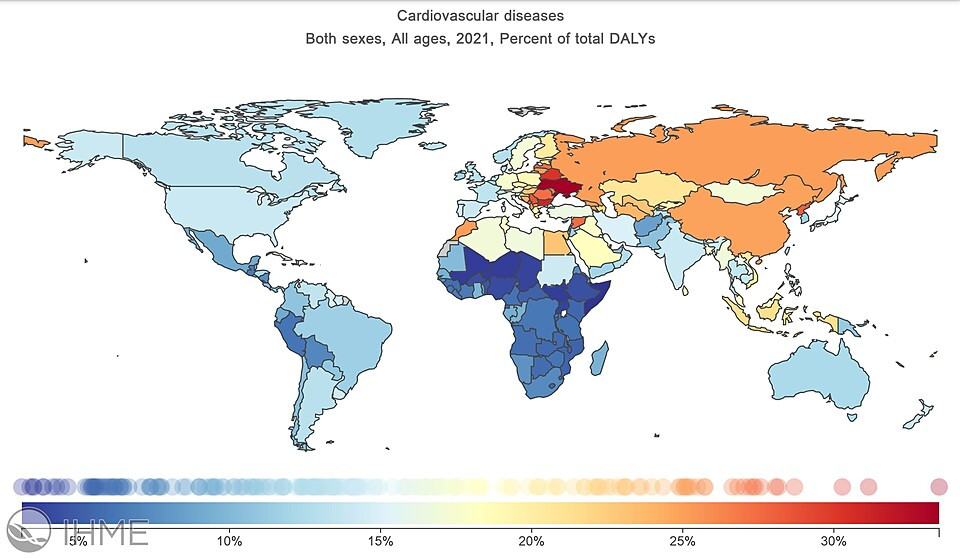

CVDs are the leading cause of death globally. The burden is not limited to high-income countries, as over three quarters of CVD deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.5

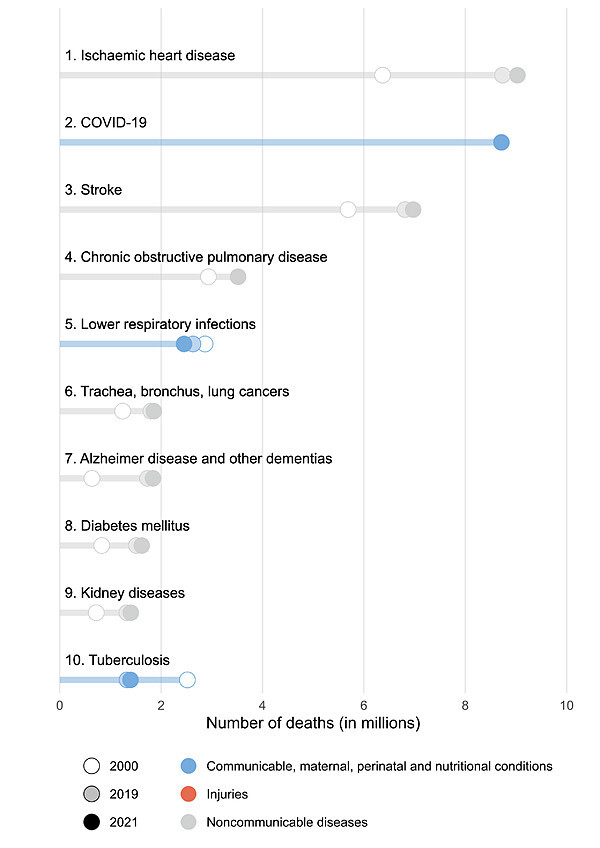

Leading Causes of Death Globally

In most years, ischemic heart disease and stroke are the top two causes of death globally. In 2021, COVID-19 caused more deaths than stroke.7 Ischemic heart disease is a term for various heart problems caused by narrowing coronary arteries, such as CAD.8

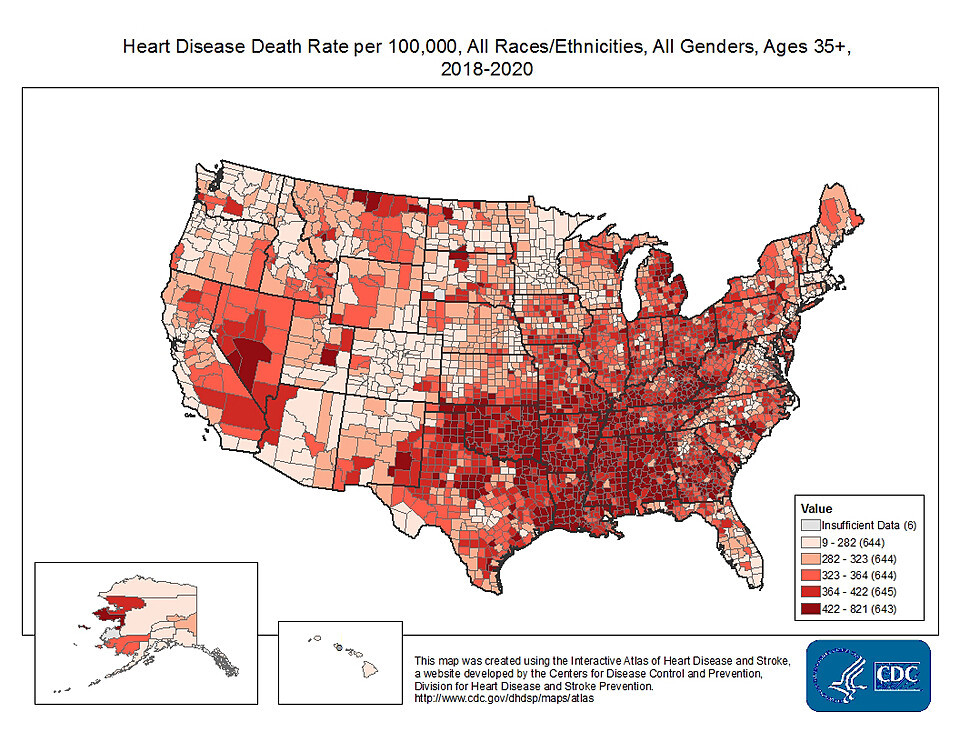

In the United States, CVD is the leading cause of death, accounting for over 900,000 deaths in 2021.12 CVD causes almost one in five deaths—a rate still slightly above the cancer mortality rate.13

Source: CDC.14

Trends in Cardiovascular Disease

Rates of CVD are increasing worldwide. One reason for this rise is low- and middle-income countries' success in preventing and treating communicable diseases such as malaria and influenza. Because risk for CVD increases as we age, rates rise as people live longer. However, other factors also contribute to rising rates, such as increasing rates of smoking, physical inactivity, poor diet, and hypertension—all known CVD risk factors.15

In high-income countries, deaths from cardiovascular disease have been falling for decades. A 2015 study surmised that recent declines in CVD rates in high-income countries "are probably due to the combined effect of birth cohorts' decreased exposure to tobacco smoking, improvements in diet, and improved treatment of cardiovascular disease and cardiometabolic risk factors targeting the prevention of cardiovascular disease, and improved treatment of cardiovascular disease."16

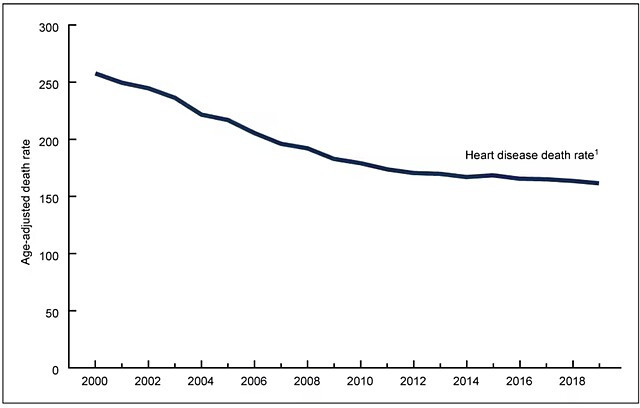

In the United States, mortality rates peaked in the 1950s and 1960s and since then have fallen. Age-adjusted mortality decreased 30 percent for heart disease and 36 percent for stroke from 2000 to 2010, but the declines in these rates slowed after 2011.17 Mortality increased again after 2019. This is likely a consequence of direct and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase persisted into 2022, the most recent year for which data are available.18

Age-Adjusted Heart Disease Death Rate, United States, 2000–2019.

Source: NCHS.19

Several factors have contributed to the decrease in cardiovascular mortality in the US:20

- Improvements to medical treatment of CVD and its precursors

- Better management of blood pressure and cholesterol

- Lower rates of smoking

- Improved physical activity

Costs of Cardiovascular Disease

A 2010 report by the Harvard School of Public Health estimated that CVD worldwide was responsible for $863 billion in costs per year from medical costs and loss of life-years and productivity. The authors of that report projected that these costs could rise to $1.044 trillion ($1,044,000,000,000) by 2030.21

Environmental Drivers of CVD

This table summarizes various lifestyle, medical, and toxicant exposure risk factors for cardiovascular disease, many of which are discussed in more detail following the table. References for lifestyle and medical risk factors are included in the discussions below. All toxicant listings are from CHE's Toxicant and Disease Database except as noted.

|

Disease or Condition |

Lifestyle / Medical Risk Factors |

Toxicants |

|

|

Strong Evidence* |

Good Evidence* |

||

|

Arrhythmias |

|

|

|

|

Cardiomyopathy |

|

|

|

|

Coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, atherosclerosis |

|

|

|

|

Heart attack (myocardial infarction) |

|

|

|

|

Heart failure |

|

|

|

|

High blood pressure (hypertension) |

|

|

|

|

Stroke (cerebrovascular disease) |

|

|

|

*"Strong evidence" and "good evidence" are described on our About the Toxicant and Disease Database webpage.

While evidence indicates that individually modifiable lifestyle factors (high blood pressure, diet, physical activity and tobacco smoke) are more significant than chemical exposures in increasing CVD risk,37 a 2016 report from the World Health Organization estimated that 35 percent of the global burden of ischemic heart disease in disability-adjusted life years lost (DALYs) are attributable to environmental exposures, especially these:38

- Indoor and outdoor air pollution

- Secondhand tobacco smoke

- Lead

One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health. DALYs for a disease or health condition are the sum of the years of life lost to due to premature mortality (YLLs) and the years lived with a disability (YLDs) due to prevalent cases of the disease or health condition in a population; see Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). WHO’s report also concluded that 42 percent of stroke-related DALYs are attributable to the environment, primarily indoor and outdoor air pollution (including ozone and secondhand tobacco smoke); lead; job strain; chemicals such as PCBs, dioxins, phthalates and pesticides; and radiation.39 Clearly, environmental exposures are significant contributors to CVD.

Air Pollution

Particulate matter pollution — from combustion (burning of wood, fossil fuels and other materials), mining, dust, and other sources, and often in combination with gases such as nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide — is a primary environmental contributor to cardiovascular disease risk.40 Particulates are a hazard both indoors and outdoors. Research has found that exposure to increased concentrations of particulate matter over a few hours to weeks can trigger cardiovascular disease-related heart attacks and death. Longer-term exposure also increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and decreases in life expectancy.41 See our Environmental Hazards pages for information on sources of pollution.

A 2014 report from the World Health Organization on air pollution estimated that globally seven million deaths were associated with both indoor and outdoor air pollution in 2012, with the majority of those coming from cardiovascular disease, primarily ischemic heart disease and stroke.42 Fine particle pollution has been associated with risk of ischemic heart disease, arrhythmias, heart failure, and cardiac arrest, in addition to overall cardiovascular mortality.43 Exposure to ambient air pollution can reduce life expectancy up to several years and was responsible for approximately 24 percent of the global burden of ischemic heart disease (in disability-adjusted life years) in 2012.44

Exposure to pollution appears to increase both the immediate and longer-term risks of cardiovascular events. Studies suggest that air pollution can activate inflammatory pathways—leading to atherosclerosis—and interfere with heart rhythm.45

Secondhand Smoke and Indoor Smoke

Secondhand smoke, or environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), can influence the cardiovascular system in several ways: increasing inflammation, insulin resistance and arterial resistance, and decreasing HDL cholesterol (“good” cholesterol) levels.46 ETS can also increase platelet aggregation, increasing the risk of blood clots.47

Although secondhand smoke may seem less serious than active smoking, effects are seen even at these lower exposure levels.48 Aggregated results of dozens of studies looking at the effects of secondhand smoke on cardiovascular disease show an increased risk of stroke of roughly 23 percent49 and an increased risk of heart disease between 25 and 30 percent.50

Other sources of smoke in indoor air, such as cooking stoves and wood stoves, also contribute to cardiovascular disease risk, with indoor cooking stoves a substantial contributor in developing countries.51

Lead

Lead poisoning is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease risk, with several studies showing a small but significant rise of hypertension after lead exposure.52 Lead exposure has also been associated with a significant increase in CVD mortality, myocardial infarction (heart attack), stroke, ischemic heart disease, and atherosclerosis.53 The World Health Organization estimates that lead exposure was responsible for over 800,000 deaths from CVD in 2019.54

Other Environmental Drivers

Other exposures that also contribute to risk include arsenic, persistent organic pollutants, noise, stress, the design of the built environment, and extreme temperatures.

Arsenic

Long-term exposure to high levels of arsenic in drinking water has been associated with a thickening of small and medium-sized arteries in children and young adults and may increase the risk of CVD-related death, although evidence to date is not conclusive.55

Cadmium

Some evidence indicates that much of the increased risk of peripheral arterial disease arising from smoking results from exposure to cadmium in cigarettes.56 A 2013 review of the health effects of cadmium exposure showed elevated risks of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease.57 Evidence suggests that cadmium may act to increase CVD risk through atherosclerosis, initiating the buildup of plaques in the arteries.58

Lifestyle Factors

Lifestyle factors are the most important individually modifiable risk factors for CVD. These include an unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and tobacco and alcohol use. Others, including stress and infectious disease, can also be important risk factors.

Nutrition

Nutrition is among the most important factors influencing heart health. Diet not only influences weight and obesity but can have strong impacts on insulin sensitivity and diabetes, inflammation throughout the body, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, and oxidative stress, among others.60 While new research on dietary health is ongoing, and recommendations continue to evolve, researchers have enough understanding of how most foods can improve or impair cardiovascular health to provide evidence-based advice.

Dietary choices are not only due to individual preferences but are promoted or restricted by environmental and societal factors:

- Foods high in fat and sugar are often cheaper or more readily prepared than vegetables and whole grains. This is in part because current agricultural policies promote the production of refined grains and foods that are highly processed, sugary, and contain unhealthy fats, rather than healthier choices such as vegetables and fruits.

- The availability and affordability of fresh fruits and vegetables can vary widely by neighborhood, influenced by socioeconomic status and ethnicity. The existence of "food deserts" with limited or no access to fresh food limits neighborhood access to nutritious choices.61 See our Agriculture, Food, & Soil webpage for more information on both agricultural policy and food availability.

- The ability of individuals to pay for sufficient and nutritious food is influenced by economic systems where they live. Research has shown that people living with food insecurity – limited access to nutritious food – have an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.62

- Advertisements and cultural influences can also shift people towards or away from particular foods.

Physical Inactivity

Physical inactivity is one of the leading preventable risk factors for high blood pressure.63 Physical inactivity is also associated with a 24% increase in risk of coronary heart disease and a 16% increase in risk of stroke.64

Tobacco Smoking/Vaping

Tobacco smoking is well established as a contributor to cardiovascular disease risk. Smoking-induced cardiac damage comes from two major mechanisms: direct adverse effects on the myocardium and indirect effects on the myocardium through comorbidities such as atherosclerotic plaques in coronary arteries and hypertension that eventually damage and remodel the heart.65

The use of e-cigarettes (vaping) has been shown to have similar risks to cardiovascular health.66

Alcohol Consumption

Whether light or moderate alcohol consumption may have modest beneficial effects regarding ischemic heart disease and ischemic stroke is open to debate. But, occasions of heavy drinking—both sporadic and chronic—clearly increase the risk of most major cardiovascular disease categories.67

Other CVD Risk Factors

Infectious Disease

Well established links exist between CVD and some infectious diseases, possibly because systemic inflammation seen in infections can have damaging effects on blood vessels and the heart, increasing the risk for heart disease later in life:

- Periodontal disease—an infection of the gum tissue often precipitated by poor oral hygiene—has been associated with cardiovascular disease, although it is not clear whether the infection causes CVD itself.68

- Inflammation throughout the body as seen in herpes simplex 1 and Chlamydia pneumoniae may increase risk for cardiovascular disease.69

- People living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have a greater risk of CVD.70

- COVID-19 is known to increase the risk of heart attack and stroke for up to a year after infection.71

Stress

The body’s normal stress response can include increases in blood pressure, heart rate, and blood glucose. When the stressor passes or is resolved, the body should return to its previous state. With repeated or chronic stress, the body’s ability to regulate the stress response is impaired. Chronic stress can lead to a greater risk of developing high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and coronary heart disease.72 This process is explained in more detail on our Psychosocial Environment webpage.

Common contributors to chronic stress include:

- Poverty and socioeconomic stress

- Community violence and/or crime

- Household violence

- Housing instability

- Discrimination/perceived racism

- Work-related stresses

- Adverse childhood experiences

A 2006 study found that levels of stress hormones are significantly higher among those of lower socioeconomic status, independent of race and age. Perception of discrimination can also lead to chronic stress, associated with higher blood pressure among both adults and children.73

Comorbidities

Several comorbidities are important for assessing cardiovascular disease risk.

- People with diabetes develop cardiovascular disease at greater rates than those without diabetes, and those who develop cardiovascular disease tend to have poorer prognoses than those without diabetes.74

- Individuals with metabolic syndrome have a 53 percent increase in risk of developing CVD and 75 percent increase in risk of death from CVD.75

- High blood pressure can injure blood vessels, increasing the risk of stroke, atherosclerosis, and other cardiovascular diseases.76

- Kidney disease is both a cause and a consequence of cardiovascular disease. Risk of death from cardiovascular disease can be 10 to 30 times greater in dialysis patients compared to the regular population.77

Metabolic syndrome is a collection of conditions that sharply increase a person’s risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes and stroke.78

People with three or more of the following conditions are considered to have metabolic syndrome:

- Abdominal obesity, as excess fat in the stomach area is a greater risk factor for heart disease than excess fat in other parts of the body, such as on the hips. A waistline of 40 inches or more in men or of 35 inches or more in women is considered a risk.

- Fasting blood glucose levels above 100mg/dL

- Elevated blood pressure, with either systolic blood pressure above 130 or diastolic blood pressure above 85.

- High levels of triglycerides in the blood, over 150mg/dL

- Low HDL cholesterol levels, below 40g/dL in women or below 50g/dL in men

Prevention and Policy

The risks and exposures related to cardiovascular diseases are interrelated and interconnected. For instance, a person’s race can influence exposure to microaggressions and discrimination that then cause stress. Access to education can influence social status, earning power, the ability to afford adequate housing and food, and more. These factors influence exposures and opportunities in the community, at workplace, in personal relationships, and in the home environment.

These factors can also contribute to personal choices that influence health. Addressing these interconnected factors individually, at any level, will contribute to CVD prevention. However, multilevel approaches will be more successful, as demonstrated in Finland’s North Karelia project. In the 1970s, N. Karelia had the highest cardiovascular mortality rates in the world, but population-based preventive measures through changes in lifestyle and the community environment dramatically reduced their incidence.79

Although cardiovascular disease is an enormous worldwide public health threat, opportunities to improve heart health and prevent CVD are available at the personal, community, national, and global levels.

Regional, National, and International Prevention

Cities, counties, states, and countries can influence cardiovascular health at the population level by promoting and enabling beneficial individual activities and by regulating harmful factors.

Promoting Healthier Diets

The structure of food production systems can promote healthier eating. Governmental subsidies, taxes, and regulations can have tremendous influence on the availability of both healthy choices (fresh fruits and vegetables) and unhealthy choices (refined grains and foods high in sugar and unhealthy fat; ultra-processed foods). Some examples of how policy influences food choices:

- In 2012, the US Department of Agriculture updated the minimum nutritional standards for the national school breakfast and lunch programs to align with current nutritional science regarding a healthy diet for children across different age groups.80

- Federal agricultural policies have contributed to dramatic changes in the US food supply since the 1930s, encouraging overproduction of commodity grain and oilseed crops such as corn and soybeans. Subsidies have fueled the rise of these calorie-dense crops in our food supply in the form of added fats and sugars, and their cheap availability as feed for livestock has contributed to an increase in less-healthy meat and dairy choices.81 Shifting subsidies and incentives toward more nutrient-dense food choices could bring the prices of these foods down and promote more healthy eating.

- The 2010 federal Affordable Care Act includes provisions requiring large retail food chains and vending machine operators to disclose calorie content of items on menus and in machines and also provide other important nutritional information.82

- Some localities have used zoning or licensing laws and incentive programs to regulate the location and density of fast food outlets or to promote the availability of healthy foods in neighborhood corner stores.83

- Cities, states, or federal agencies have set minimum nutrition standards for foods served in child care settings, regulated the use of trans fats, or taxed sugary beverages to decrease consumption rates.84 Early research shows that taxing unhealthy food choices reduces their consumption.85 In 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration banned trans fats specifically to reduce coronary heart disease and prevent thousands of fatal heart attacks every year.86

Encouraging Physical Activity

The design or retrofitting of buildings, neighborhoods, and transportation systems can encourage physical activity:

- The inclusion of safe, accessible stairways as an alternative to elevators, as well as other innovations in building design87

- Adding inviting parks, trails, and playgrounds to neighborhoods, and enhancing the safety and attractiveness of public walkways88

- Providing safe, convenient public transit89

- Building bicycle lanes or trails90

See more about how the built environment influences physical activity on our Built Environment webpage. Increasing active transportation at the population level can also provide extra benefits from reduced air pollution.

Decreasing Cigarette Smoking and Secondhand Smoke

The following policy actions, supported by the American Heart Association in a 2016 policy statement, are all associated with lower smoking rates in a population.91 These policies can also decrease exposure to secondhand smoke:92

- Bans on public and workplace smoking

- Tobacco excise taxes

- Funding for tobacco cessation and prevention programs

- Advocating for greater insurance coverage for smoking cessation programs

- Raising the minimum age for purchasing tobacco products

As of 2023, 35 states have adopted smoke-free laws for bars, restaurants, and worksites.93 A 2012 study aggregating the effects of many smoke-free policies throughout the US shows a 39 percent decrease in chest pain, coronary heart disease, and sudden cardiac death, as well as roughly 15 percent decrease in myocardial infarction, coronary syndrome, coronary events, ischemic heart disease, and stroke.94 A review done in 2023 found that smoke-free legislation was associated with approximately 9% to 10% reduced odds of overall CVD events.95

Discouraging Alcohol Use

Regulatory efforts to reduce excessive consumption of alcohol show promise in improving cardiovascular health.96

Reducing Air Pollution

In the US, National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) were established with the 1990 Clean Air Act, with the primary goal of protecting public health, particularly for groups at greater risk, including children and the elderly. These standards are updated every five years to ensure they keep pace with our scientific understanding of the risks of air pollution. The American Heart Association supports full implementation of the Clean Air Act, tightening regulation of sources of air pollution, and other measures to reduce air pollution, both indoors and outdoors.97

The 2020 policy statement from the American Heart Association on air pollutants highlights the need for policies to reduce harmful exposures:

“Policy options to mitigate the adverse health impacts of air pollutants must include the reduction of emissions through action on air quality, vehicle emissions, and renewable portfolio standards, taking into account racial, ethnic, and economic inequality in air pollutant exposure. Policy interventions to improve air quality can also be in alignment with policies that benefit community and transportation infrastructure, sustainable food systems, reduction in climate forcing agents, and reduction in wildfires. The health care sector has a leadership role in adopting policies to contribute to improved environmental air quality as well.”98

Regulations to monitor and reduce air pollution have been extremely effective in decreasing CVD risk in the US. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that over 230,000 deaths were prevented in 2020 because of Clean Air Act regulations of fine particulates and ozone.99

Reducing Chemical and Other Exposures

To date, typical discussions of prevention interventions focus heavily on lifestyle risk factors.100 However, addressing all contributors to cardiovascular disease risk, including harmful chemicals, pollutants, and other relevant exposures is necessary to prevent avoidable disease and death.

Policy initiatives to reduce hazardous chemical, radiation, noise, and other potentially harmful exposures could also reap cardiovascular benefits. UCSF’s Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment recently published recommendations to protect people and communities from harmful chemicals. Following these recommendations would strengthen our systems of chemical regulation and help prevent CVD as well as other conditions.

Personal Prevention

The systemic changes outlined above are necessary for more comprehensive prevention of CVD, but there are actions that individuals can take now to reduce their personal risk.

Choosing Healthier Diets

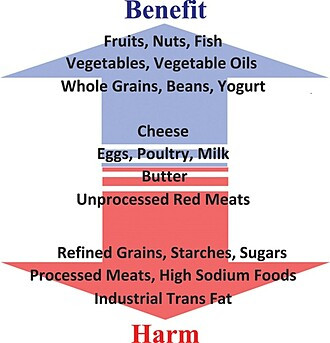

Because diet is among the most important determinants of CVD risk, CVD-prevention efforts must address dietary choices. Particularly effective is a diet with a variety of fruits, vegetables, unsaturated vegetable oils, whole grains, nuts, beans, and fish that are low in mercury and other contaminants.101 A heart-healthy diet is also low in sugars, red and processed meats, and refined grains. The American Heart Association publishes diet and lifestyle recommendations.

Research has revealed that focusing on a single aspect of diet—such as “low-fat” or “low-carb” options—does not produce much benefit to cardiovascular health. Not all fats have the same effect on CVD risk, and not all carbohydrates influence health equally. Focusing on the whole diet is more productive.102

The PREDIMED trial in 2013 was conducted among participants at high risk of CVD because of diabetes and/or additional risk factors but without known heart disease at the time of enrollment. Some participants were advised to follow a Mediterranean diet featuring fish, vegetables, fruit, white meats and given extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) and nuts as well.

Control participants were advised to consume a low fat diet without other restrictions. Those participants following the Mediterranean diet plus EVOO and nuts saw nearly 30 percent fewer major cardiovascular events when compared to participants following a low-fat diet after an average follow-up period of 4.8 years.103 Other dietary patterns are also effective for promoting heart health.104 There is general agreement that diets high in sugar, sodium, refined grains, and industrial trans fats, while low in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are harmful to cardiovascular health, increasing the risk of heart disease and stroke.105

Purchasing organic fruits and vegetables when possible can help reduce exposure to pesticides, many of which are associated with various health harms.

Increasing Physical Activity

Just 30 minutes of walking per day is associated with a lower risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and overall cardiovascular disease.106 The World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control, and the American Heart Association all recommend these levels of physical activity at a minimum each week for adults 18-64:107

- 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, or some comparable combination of these.

- Two muscle-strengthening activities that work all major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms).

These guidelines are adjusted for children, for older adults, and for pregnant and postpartum women. Please see the CDC guidelines for more information.

Eliminating Cigarette Smoking and Reducing Alcohol Use

Well-established data show that refraining from smoking and exposures to secondhand smoke will reduce lifetime risk of CVD. Because exposures can start before birth and continue throughout childhood, families and entire households—and not just individuals—need to address cigarette smoking at home.108 Eliminating excessive alcohol consumption, even just occasional heavy drinking, also reduces risk. The American Heart Association does not recommend any alcohol consumption.109

Avoiding Chemicals and Other Exposures

Reducing personal exposures to noise, air pollution, and chemicals listed in the table above will reduce CVD risk. More information about sources of exposure and avoiding those exposures is published on our related webpages, available through the links in the table.

Prevention and Lifetime Risk of CVD

The concept of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) outlines the important role played by environmental exposures and nutrition during pregnancy and early childhood. Underlying DOHaD is the idea that environmental exposures in utero or early in a child's life can have wide-ranging and long-term effects on cardiovascular health in adulthood.

Other factors, such as chronic stress, or other adverse child experiences, such as housing instability, childhood maltreatment, or regular discrimination can also increase the risk of CVD beginning in early adulthood and continuing throughout the lifecourse.110 This all indicates the inadequacy of treating CVD exclusively in adults, only after they are at high risk for the disease or have been diagnosed. Resources could be effectively aimed at decreasing childhood exposure to CVD risk factors early in life, rather than simply treating the disease after it arises.

Created by Nancy Hepp and Tom Austin from several sources.111

This page was last revised in June 2024 by CHE’s Science Writer Matt Lilley, with input from Ted Schettler, MD, MPH, and editing support from CHE Director Kristin Schafer.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.