Environmental exposures play a significant role in both the development of asthma and as triggers of asthma episodes, called asthma attacks. Though people with asthma have similar symptoms, the origins and triggers of the disease may differ considerably from person to person.

Multiple factors contribute to the development of asthma, including:

- Genetic predisposition, often manifested in a family history of asthma or allergies.

- Exposures in the home, school, workplace, or outdoors to environmental agents, including chemicals in products and air pollution.

- Exposure to biologic agents, such as some viruses and allergens.1

Some social determinants of health, including obesity and psychosocial stress, along with dietary factors, have also been implicated in the development of asthma. Structural racism is a root cause of many of the conditions that elevate risk factors for asthma.2 There is increasing attention by researchers to the interactions among risk factors, both genetic and exogenous.3

Asthma Prevalence and Trends

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that affects an estimated 262 million people worldwide.4 In the US, an estimated 25 million people have asthma.5

The total annual cost of asthma in the US was estimated at approximately $81.9 billion as of 2013, including direct medical expenses, lost school and work days, and early deaths.6 Almost all of the 10 deaths from asthma per day in the US are preventable.7 According to the American Lung Association, asthma is one of the most common chronic disorders in childhood and a leading cause of hospitalization in children, as well as one of the leading causes of school absenteeism.8

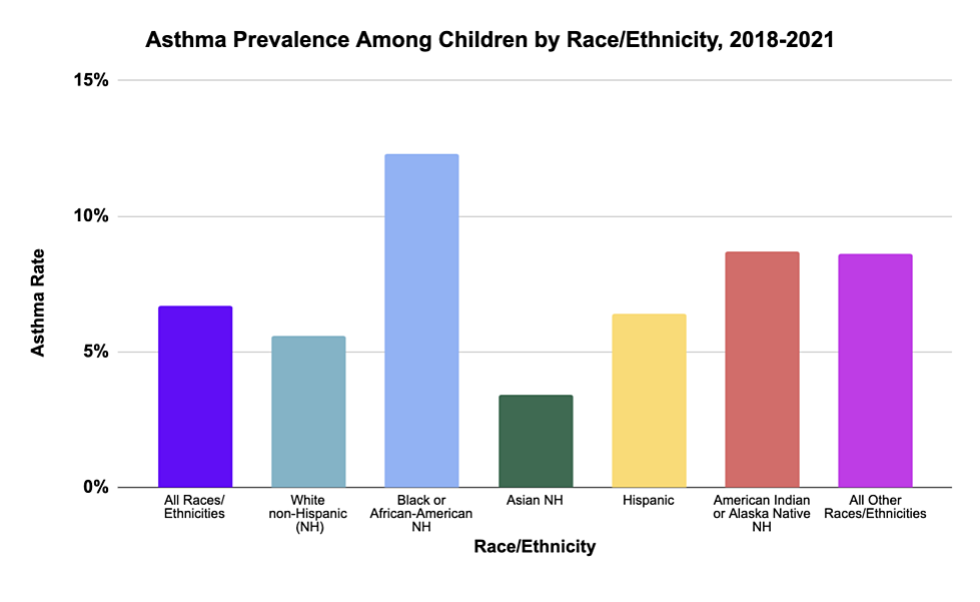

In the US, racial and socioeconomic disparities with regard to asthma are dramatic.9 Black children, for example, have two times the prevalence of asthma compared to white children. Black children are over seven times more likely to die of asthma than white children.10

These disparities are driven by structural racism and social determinants of health — they are not only unequal, but also fueled by factors and conditions that are unjust.11 Asthma disparities by race hold true across economic strata and in urban as well as rural communities.12 Higher exposures to structural, social, and environmental risk factors contribute to these disparities. For example, moisture causing mold or cockroach infestations, both of which can trigger asthma attacks, are more prevalent in multi-unit housing projects that are not well-maintained by landlords; residents in this poor quality housing are disproportionately low income.13 In some places, people experiencing higher rates of asthma have less access to high quality health care.14

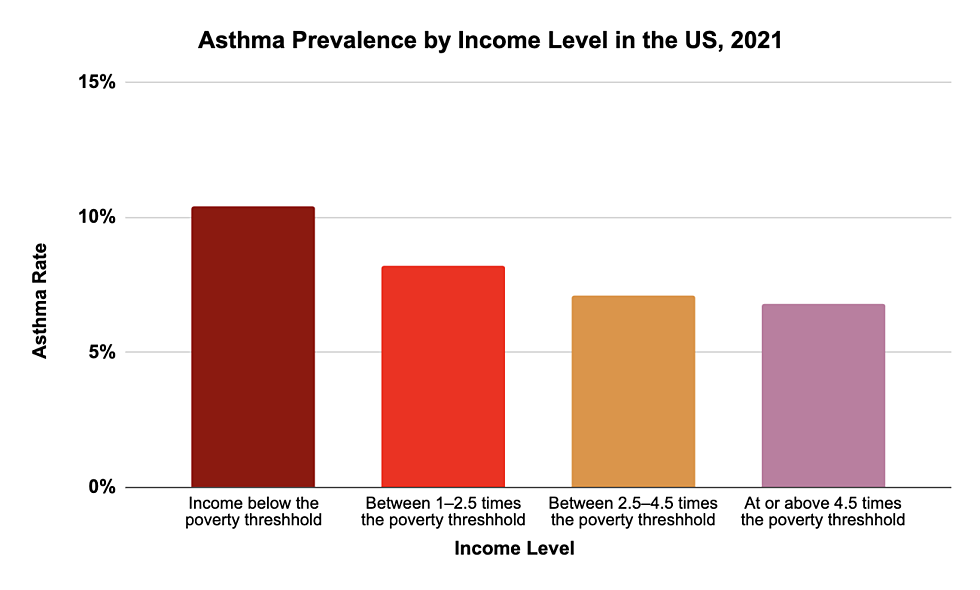

The prevalence of asthma is also higher among persons with family income below the poverty level.16

Environmental Drivers of Asthma

Asthmagens are agents that act in combination with other factors to initiate or cause asthma in someone who did not previously have the disease. Asthmagens are generally categorized as either sensitizers or irritants, based on the pathway by which they initiate asthma.

- Sensitizer-induced asthma (also known as allergen-induced asthma or immunologic asthma) involves an immune system response to a chemical or biologic exposure. Agents include biologic agents (such as pet allergen, mold, dust-mite, and cockroach allergens) or chemicals such as gluteraldehyde (found in some cleaning agents).18 This is the most common form of asthma and is strongly linked to family history. Sensitizer-induced asthma is characterized by an asymptomatic period of sensitization. Although the immunologic mechanism is not known for all agents, many sensitizers (allergens) produce asthma through an immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated mechanism.

- Irritant-induced asthma develops most often from relatively high one-time exposures to agents classified as irritants (for example, tobacco and irritant chemicals such as acids). Irritant asthma does not involve the immune system, although individuals may experience the same symptoms (coughing, wheeze, breathlessness, and so on). Since irritant-induced asthma is not mediated by the immune system, allergic sensitization does not occur, and asthma may be caused from a single exposure to the irritant.

After asthma develops, exposures to a variety of allergens or irritants can trigger or exacerbate an asthma attack.

Asthmagens that cause asthma are distinct from triggers of asthma (exposures that cause an asthma attack or make it worse).

Many environmental exposures are capable of both initiating new-onset asthma and triggering asthma attacks. For example, tobacco smoke and traffic-related air pollution can both cause the initial onset of asthma in people who previously did not have the disorder, as well as trigger asthma attacks in people already diagnosed.

Just as a different mix of risk factors may contribute to the development of asthma in one person versus another, the exposures that will trigger an asthma attack differ between individuals.

Environmental Risk Factors for Asthma Development

Environmental exposures — both sensitizers and irritants — associated with the initial onset of asthma include:

- Tobacco smoke (for both the smoker and non-smokers exposed to environmental tobacco smoke)

- Various biological allergens (for example some pest and pet danders, dust mites, and some species of mold)19

- Chemicals (including, for example, cleaning agents such as bleach and gluteraldehyde)

- Traffic-related air pollution

There is solid evidence that psychosocial stress and obesity20 — both of which can derive from environmental exposures and conditions — also contribute to the development of asthma. For example, obesogens are a class of hormone-disrupting chemicals found in many consumer products. These obesogens induce the production of fat cells in the body and make people more likely to develop obesity.

The Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics has identified over 400 agents capable of causing asthma in workplace settings.21 Many of the chemicals shown to cause asthma in workers have not been studied in other populations, such as in children. However, it is likely that these chemicals do cause asthma outside of the workplace. For example, formaldehyde is a known cause of occupational asthma. A systematic review concluded that formaldehyde exposure is also positively associated with childhood asthma.22

Working parents can bring exposures home to children on clothing and in other ways, so parents and pediatricians should consider occupational exposures when assessing causes and triggers for children.

Gene-Environment Interactions in Asthma Development

Interactions among genes and environmental risk factors are likely to be important in the development of asthma, as demonstrated by research that considers genetic make-up as well as exposure to traffic-related air pollution. Several studies comparing rates of new cases of asthma among children living near a busy roadway to children living farther away suggest that near-roadway exposures early in life increase the risk of asthma by as much as 2.5 times.23

When genetic make-up is considered, the relative risk of developing asthma among children living near a busy roadway can be magnified. For example, glutathione S-transferase (GST) and epoxide hydrolase (EPHX1) are enzymes involved in detoxification and elimination of chemicals like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Certain genetic variants in GST and EPHX1 are individually associated with increased risk of developing asthma.24

A 2007 study found that a variant in the gene EPHX1 increased the risk of asthma by 50 percent. That variant plus a variant of GST increased the risk of asthma four-fold. And those two variants plus living near a major roadway increased the risk by nine-fold, compared to people with neither variant who did not live near a major roadway.25

Some but not all more recent studies have confirmed specific GST variants associated with increased asthma risk after exposure to traffic-related air pollution and tobacco smoke. Inconsistencies in study findings may be due to differences in the role of genetics in childhood- vs. adult-onset asthma, as well as combinations of a larger number of genes that can influence risk.26

Environmental Risk Factors for Asthma Exacerbations

Many substances that can cause new onset asthma can also trigger asthma attacks in people already diagnosed with the disease. Environmental risk factors that exacerbate asthma symptoms include these:27

- Chemical sensitizers and irritants used in manufacturing and other workplaces

- Tobacco smoke and outdoor air pollutants that infiltrate the indoor environment

- Some pesticides

- Allergens including mold, pollen, cockroach droppings, and dander from pets and rodents

- Exercise and cold weather

- Outdoor air pollution, including traffic-related air pollution and pollution from industrial sources

- Family and community stressors/psychosocial stress

Interactions among different exposures may be important in the exacerbation of asthma. For example, a 2003 study found that asthma symptoms in children ill with a respiratory virus are likely to be more severe if the children are exposed to nitrogen dioxide, even at levels below current air quality standards.28 In a study from 2011, combining exposure to low levels of pollen with exposure to urban air pollution dramatically worsened asthma symptoms.29 Allergens and environmental tobacco smoke have also been shown to potentially interact to worsen symptoms.30

A 2021 study that focused on air pollution mixtures identified several toxic combinations associated with asthma. Many of the chemicals in the combinations were not individually associated with asthma, but were associated when in mixtures with other air pollutants.31

Recently, interest has increased in studying a number of asthma risk factors (more than two) in various combinations in order to determine how they collectively influence outcomes.32 These studies are difficult to design but new methods for multi-exposure analyses may help identify multi-pronged approaches to preventing asthma onset and asthma attacks.

Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Asthma

Traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) is a complex mixture of particulate matter and other chemicals derived from combustion, non-combustion, and primary gaseous sources. Increasing evidence suggests that long-term exposures to TRAP and its surrogate, nitrogen dioxide, can contribute to new-onset asthma in both children and adults.33 Components of diesel exhaust may also cause asthma, shown by studies finding that children growing up along streets with heavy truck traffic are more likely to develop asthma-related respiratory symptoms.34 Researchers have also found that reductions in air pollution levels, specifically nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter, were related to lower rates of new-onset asthma in children.35 36

A 2023 zip-code level ecologic study in California found that higher adoption of electric vehicles was associated with a measured reduction in nitrogen dioxide levels and fewer emergency department visits for asthma.37 This real-world study confirms some of the many anticipated health benefits from reductions in TRAP.

Exposure to vehicle exhaust and other forms of air pollution is known to trigger asthma attacks in people with the disease. Common air pollutants that exacerbate asthma include these:

- Ozone

- Nitrogen dioxide

- Sulfur dioxide (from vehicles that burn fuels with a high sulfur content)

- Particulate matter (PM5)

Climate Change and Asthma

As carbon dioxide (CO2) levels rise and temperatures increase due to climate change, both ground-level ozone and airborne pollen levels are increasing.38 The combination of higher levels of asthma-related air pollutants and allergens associated with changes in atmospheric conditions is expected to continue to increase the frequency of asthma attacks in people with asthma. These conditions may also increase rates of new onset asthma. An EPA report from 2023 found that new annual cases of asthma could increase by 4% to 11% at 2°C and 4°C of global warming, respectively.39

Effects of climate change on asthma include:

- Increased levels of ozone (O3)and fine particulate matter (such as PM5) can trigger inflammation of the lungs and reduce lung function, causing chest pain and coughing.40 “New diagnoses of asthma associated with PM2.5 and O3 exposure are estimated to increase by 34,500 (27,900 to 42,800) per year at 2°C of global warming up to 89,600 (74,100 to 108,000) at 4°C.”41

- Increasing carbon dioxide concentrations affect the timing of allergen distribution, amplifying the allergenicity of pollen and mold spores.42

- Longer growing seasons for plant-related allergens will produce more airborne allergens and could lead to more asthma attacks worldwide, including for 10 million Americans with allergic asthma.43

- Increasing precipitation and flooding due to climate change can increase mold spores, an asthma trigger and a likely risk factor for the initial onset of asthma.44

- Increasing frequency of droughts can increase dust and particulate matter, which are both causes and triggers of asthma.45

- Increasing smoke from wildfires due to climate change are likely to exacerbate asthma and increase asthma emergency department and hospital visits.46

Family and Community Stressors/Psychosocial Stress

Family and community stressors such as financial problems, divorce, exposure to violence at home or in the community, and structural racism can make children more susceptible to many health problems, including asthma. There is solid evidence that psychosocial stress contributes to the initial onset of asthma, especially when combined with other risk factors.47

Stress can also trigger asthma in people with the disease. Stress can add to and even magnify the impacts of exposure to other environmental conditions that foster the onset or increase the severity of asthma.48

Protective Factors & Prevention Strategies

Certain environmental exposures and conditions can protect against onset or symptoms:

- Exposure to microbial diversity in the perinatal period may diminish the development of asthma symptoms.49

- Breastfed infants are less likely to develop asthma and allergies compared to those fed infant formula.50 Breastfeeding enhances immune function.

- Higher vitamin D intake during pregnancy is associated with decreased risk of wheeze in early childhood. Reduced risk of wheezing may be due to reduced frequency of respiratory infections.51

- Higher vitamin D levels have also been linked to fewer asthma symptoms in obese children.52

- A healthy microbiome full of good bacteria and other microbes promotes the immune system’s ability to fight off pathogens. Broad exposure to a wealth of non-pathogenic microorganisms early in life is associated with protection against many health conditions. Studies have found that first-year infants exposed to house dust high in levels of mouse, cockroach, or cat allergens along with a variety of bacteria report significantly lower rates of allergies and recurrent wheeze at age three.53

Preventing New Cases of Asthma

Asthma death rates have decreased in the last 20 years. Asthma prevalence increased from 2001 to 2010 but has remained stable since then.54 This progress could be at least partially attributed to recent multi-factorial public health programs aimed at prevention.

There have been relatively few studies examining the most effective interventions for preventing the development of asthma. Nonetheless, measures to reduce exposures to risk factors are likely to prevent new cases and to reduce exacerbations across a population. Because asthma is a multifactorial disease, the origins of which may vary from person to person, multifactorial interventions are likely to be most effective.

For example, a Cochrane review of seven studies targeting women at high risk of having a child who develops asthma concluded that nutritional interventions combined with environmental trigger reduction reduced the risk of the child developing asthma by 50 percent. The review also concluded that multifactorial interventions were more effective than single-factor interventions.55

Other studies, focusing on women at high risk of having a child who develops asthma, have examined the impact of vitamin D or omega 3 long-chain fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy. These studies found less wheezing in their preschool children but no less asthma when they reached school age.56

A 2015 review in The Lancet concluded that until the base of intervention evidence is stronger, population-wide “public health efforts should remain focused on measures with the potential to improve lung and general health," such as these:57

- Reducing tobacco smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke

- Reducing indoor and outdoor air pollution and occupational exposures to chemicals and other agents linked to asthma onset and exacerbation

- Reducing childhood obesity and encouraging a diet high in vegetables and fruit

- Improving feto-maternal health

- Encouraging breastfeeding

- Promoting childhood vaccinations

- Reducing social inequalities

Many of these public health priorities require policy changes and program investments in workplaces, homes, schools, and communities — with a particular focus on populations and neighborhoods that are disproportionately exposed.

That said, individuals can take steps to reduce priority risk factors for asthma and reduce the likelihood that they or their children will develop asthma.58 They can address:

- Smoking (including environmental tobacco smoke)

- Reduce or stop smoking

- Smoke outside/not in cars

- Traffic-related air pollution

- Limit time outdoors if the air quality is unhealthy

- Avoid exercising near high-traffic areas

- Find alternative routes to walk to school (see our Built Environment page for more information)

- Consider using a HEPA air filter in the home

- Indoor environmental quality

- Obesity

- Talk to a medical provider about weight-loss strategies that are best for you

- Strategies include routine exercise, reducing the amount of fast foods and sugar-sweetened beverages in your diet, and eating more fruits and vegetables

- When exercising, avoid high-traffic areas

- Occupational asthmagens

- Federal safety laws require your employer to provide a safe and healthy workplace

- If you feel that your workplace is unsafe and needs a confidential health and safety evaluation, you can contact OSHA or state departments of labor standards

- See the Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics list of occupational asthmagens61 to see if chemicals in your workplace are known asthmagens

These risk factor-reduction recommendations are based on expert judgment about the strength of the evidence that particular risk factors contribute to asthma onset, along with thoughtful consideration about the pros and cons of taking action when there is inherent uncertainty about how risk factors interact with individual factors to cause disease.

Preventing Asthma Attacks

National Asthma Management Guidelines detail how to prevent asthma attacks in people who already have the disease (“secondary prevention”). These guidelines include

- Regular assessment and monitoring

- Medications appropriate for the severity of an individual’s asthma

- Education for self-management

- Understanding and addressing co-morbidities

- Reducing exposure to environmental triggers

Because these elements of effective prevention of asthma attacks include both medical interventions and interventions in home, school, work, and community environments, integration of clinical care with community resources is essential. Various models for integrating clinical and non-clinical interventions have proven cost-effective, including community health workers providing in-home asthma education and environmental trigger reduction.62

The guidelines affirm that reducing exposure to environmental triggers for asthma is a critical element of preventing asthma attacks for people with asthma. Not everyone is sensitive to the same environmental triggers, but once an individual knows which triggers exacerbate her asthma, minimizing exposure is the best strategy.

As is the case with asthmagens, some environmental triggers are within the individual’s control, but many are not. Many triggers — such as mold caused by a landlord’s failure to fix a persistent leak or air pollution from a nearby bus depot — require community action and advocacy.

One recent study showed that children who move out of high-poverty neighborhoods and into low-poverty neighborhoods experienced significant improvements in their asthma symptoms. Changing their environment improved their health.63 This shows the importance and potential of policy interventions that address the root causes of asthma, especially in neighborhoods where multiple risk factors are contributing to high rates of asthma and asthma attacks.

This page was last revised in March 2024 by CHE’s Science Writer Matt Lilley, with input from Ted Schettler, MD, MPH and Polly Hoppin, ScD, and editing support from CHE Director Kristin Schafer.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.