Both what we eat and how it is produced impact our health. We provide a brief overview of how both arenas affect health.

Diet and Nutrition

World Health Organization Daily Recommendations

Fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts and whole grains with 400+ grams (five portions) of fruits and vegetables a day

Fewer than 10 percent total energy (calories) from free sugars

Fewer than 30 percent total energy from fats, with a shift in fat consumption away from saturated fats to unsaturated fats and eliminating industrial trans-fats

Less than five grams of salt (about one teaspoon), using iodized salt

Energy intake each day should correspond to energy expended

Specific recommendations during pregnancy are listed on our Reproductive Health Research and Resources page.

|

Diet is key to health. Globally, an unhealthful diet, together with a lack of physical exercise, is a leading risk factor for poor health, increasing risks for obesity, diabetes, heart disease, stroke and cancer. Consuming essential nutrients—protein, fiber, minerals, vitamins and antioxidants—is important to staying healthy for both adults and children. These nutrients are found and best consumed in a variety of foods:

- Whole grains (not highly processed)

- Fresh fruits and vegetables, but not starchy foods such as potatoes

- Legumes (lentils and beans)

- Nuts

image from Josep Folta at Creative Commons

Dietary Fats

Fat is a necessary nutrient. Many body functions rely on a supply of healthy fats, including omega-3 fatty acids such as EPA, DHA and ALA. These fats are found in many types of seafood, including fatty fish and shellfish, as well as in some vegetable oils such as canola and soy. Moderate evidence has emerged about the health benefits of consuming seafood to reduce risks of heart disease and modestly reduce symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Seafood Contaminants and Recommendations

While many varieties of fish and seafood provide necessary fatty acids and micronutrients, they are also often a source of concern due to chemical contaminants from polluted water. Fish advisories warning about contaminated fish in local waters have been posted in all 50 US states. To search for fish advisories within the US, see EPA’s interactive map of advisories.

Vulnerable populations who need to pay special attention to fish advisories:

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women

- Young children

- High consumers of fish and seafood, such as sport anglers, recreational fishers and subsistence fishers

- Elderly individuals

To promote neurodevelopment in children, pregnant and breastfeeding women should consume eight to 12 ounces of seafood a week, but avoiding seafood known to be high in mercury:

- White (albacore) tuna

- Tilefish

- Shark

- Swordfish

- King mackerel

Broiled freshwater trout, a low-mercury choice; image from Ernesto Andrade at Creative Commons

Other chemical contaminants commonly found in fish and shellfish:

94 percent of all advisories in effect in the US in 2011 involved five bioaccumulative chemical contaminants: mercury, PCBs, chlordane, dioxins, and DDT.

|

To promote fetal and infant development, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health recommends that pregnant or breastfeeding women consume eight to 12 ounces of seafood per week from a variety of seafood types that are low in methylmercury, and that children eat age-appropriate quantities after weaning. The health benefits of omega-3 dietary supplements are unclear.

Even though fat is essential, too much fat—especially saturated fats found in red meats and trans-fat in processed food—increases the risk for heart disease and stroke. Processed meats usually contain unhealthful amounts of both fats and salt. White meats such as from poultry and fish are lower in fat. Daily fat intake should provide fewer than 30 percent of total calories.

Are Organically Grown Foods Safer or More Nutritious?

To answer this question, we draw from two meta-analyses and one review article, each of which analyzed dozens to hundreds of published studies.

A 2012 review of studies from 1966 to 2011 concluded that "the published literature lacks strong evidence that organic foods are significantly more nutritious than conventional foods. Consumption of organic foods may reduce exposure to pesticide residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria." Escherichia coli contamination risk did not differ between organic and conventional produce, but the risk for isolating bacteria resistant to three or more antibiotics was higher in conventional than in organic chicken and pork.

A 2014 meta-analysis of 343 peer-reviewed publications found that "the concentrations of a range of antioxidants such as polyphenolics were found to be substantially higher in organic crops/crop-based foods." The frequency of pesticide residues was four times higher in conventional crops, which also contained significantly higher concentrations of the toxic metal cadmium." Smaller but statistically significant and biologically meaningful composition differences were also detected for a small number of carotenoids and vitamins."

A 2016 meta-analysis of 67 published studies comparing the composition of organic and non-organic meat products found that "significant differences in FA [fatty acid] profiles were detected when data from all livestock species were pooled." Organic meat had similar or slightly lower levels of unhealthful saturated fatty acids and healthful monounsaturated fatty acids. Larger differences were detected for healthful total polyunsaturated fatty acids and omega-3 fatty acids, with higher levels in organic meat.

In sum, the differences in micronutrients are not huge but can be significant for some antioxidants and vitamins. Differences in fat composition of meat products, of pesticide residues and at least one metal residue in produce are meaningful. Each of these differences can impact health.

The increased risks of bacterial contamination to human health were not described by the 2012 study authors, but they concluded that consumption of organic foods may reduce exposure to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

|

Vegetable oils including olive, sunflower, corn and soy have healthful unsaturated fats, while oils high in saturated fats include butter, ghee, lard, coconut and palm oils. Trans-fats are usually found in processed, baked and fried foods.

Micronutrients

Several micronutrients are essential for health, especially during development. We highlight some key ones here.

Iron

Iron is an essential mineral because it is needed to make hemoglobin, a part of blood cells. Iron is also essential for brain and nerve development. Low iron content (anemia) during pregnancy can increase the risk of perinatal death and low birth weight. Globally, roughly 40 percent of all children under five years old and pregnant women have an iron deficiency. A 2009 global report states that iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy is associated with 115,000 deaths each year, accounting for one-fifth of all maternal deaths. The best dietary sources of iron:

-

|

Dried fruit compote, image from Emily at Creative Commons

|

Dried beans

- Dried fruits

- Eggs (especially egg yolks)

- Iron-fortified cereals

- Liver

- Lean red meat (especially beef)

- Oysters

- Poultry (dark meat)

- Salmon

- Tuna

- Whole grains

Iodine

Iodine is needed for cells to convert food into energy and also for normal thyroid function and the production of thyroid hormones. Iodine is required for fetal brain development, and low iodine may be responsible for mental impairment in 18 million babies annually. For this reason and to prevent goiter, salt is fortified with iodine, which is available in 70 percent of the world. Dietary sources of iodine:

-

|

Cod, image from Rool Paap at Creative Commons

|

Iodized salt

- Seafood, especially cod, sea bass, haddock and perch

- Kelp

- Dairy products

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is known as retinol because it produces pigments in the retina of the eye. Vitamin A promotes good vision, especially in low light, and it may also be needed for reproduction and breastfeeding. Vitamin A is needed in forming and maintaining healthy teeth, skeletal and soft tissue, mucous membranes and skin.

The developing immune system and eyesight require vitamin A. Children with vitamin A deficiencies suffer from more blindness, measles and diarrhea than those without. Although it is an essential nutrient, one-third of all young children and one in six pregnant women have deficiencies.

Golden Rice

Golden rice has been genetically modified to contain beta-carotene. A cup of this rice provides 50 percent of the recommended daily amount of vitamin A for an adult. Developed in the early 2000s, the inventors wanted to provide golden rice as a gift to farmers in developing countries. New varieties continue to be developed on a nonprofit basis.

image from IRRI Photos at Creative Commons

Find more information about genetically modified foods further down on this page.

|

Two types of vitamin A are found in the diet:

- Preformed vitamin A, found in animal products such as meat, fish, poultry and dairy foods. Unfortunately, most animal sources of vitamin A are also high in saturated fat and cholesterol.

- Pro-vitamin A is found in plant-based foods. Precursors to vitamin A, the body converts these substances to vitamin A.

|

image from Christine Rondeau at Creative Commons

|

Beta-carotene is a naturally occurring pro-vitamin A. The richest sources of beta-carotene are yellow, orange and leafy green fruits and vegetables: carrots, spinach, lettuce, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, broccoli, cantaloupe and winter squash.

Zinc

This mineral is important for immune system function and plays a role in cell division, cell growth, wound healing and the breakdown of carbohydrates. Zinc is also important for the development of the nervous system. Those low in zinc are at a higher risk for premature birth, diarrhea, infections, poor growth and all-cause mortality. Globally, 17 percent of people have a diet insufficient in zinc. Dietary sources of zinc:

|

image from Erich Ferdinand at Creative Commons

|

- Animal proteins: beef, pork and lamb contain more zinc than fish, and dark meat of poultry has more zinc than light meat

- Nuts

- Whole grains

- Legumes such as dried beans and lentils

- Yeast

Folate

This vitamin is important for cell growth and to help the body prevent anemia. Folic acid, the synthetic form of folate, is found in supplements and added to fortified foods. Folate is essential during early fetal development, supporting healthy development of the brain, skull and spinal cord. Foods fortified with folic acid, or folic acid taken as a supplement, can reduce the risk of neural tube defects by up to 50 percent. Folic acid supplements before and during the first trimester can lower chances of miscarriage. Dietary sources of folate or folic acid:

|

Dried beans, image from Jenny Lam at Creative Commons

|

- Leafy green vegetables

- Fruits

- Dried beans, peas, and nuts

- Enriched breads, cereals and other grain products

Vitamin D

The body makes this fat-soluble vitamin when exposed to sunlight and converts it into a hormone called activated vitamin D or calcitriol. Vitamin D is essential for calcium absorption, and severe vitamin D deficiency has long been associated with rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. Both of these conditions cause soft, thin and brittle bones. More recent findings indicate that vitamin D deficiency appears to interact with incidence and progression of infectious disease—notably tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS—and possibly with immunologic and cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

Promoting a Healthful Diet

The World Health Organization suggests these approaches to improving diets:

- Incentivize food producers and sellers to provide fresh fruits and vegetables

- Restrict the food industry’s use of processed foods and foods high in free sugars, fats and salt

- Do not market alcohol to children

- Make healthy foods accessible and affordable in community spaces (schools, hospitals, workplaces)

- Consider taxing unhealthy foods

- Promote consumer awareness of a healthy diet

- Encourage culinary skills

- Make nutritional content available and accessible

- Promote a breastfeeding culture

Research indicates that access to farmer’s markets can increase fruit and vegetable consumption. |

Very few foods naturally contain vitamin D, but many are fortified with vitamin D. Dietary sources of vitamin D:

- Fatty fish, such as tuna, salmon, and mackerel

- Beef liver, cheese and egg yolks provide small amounts

- Mushrooms provide some vitamin D, but only after exposure to ultraviolet light such as sunshine

- Most milk in the United States is fortified with vitamin D, but not other dairy products such as cheese and ice cream

- Many breakfast cereals and some brands of soy beverages, orange juice, yogurt and margarine

Sugar

Diets high in added sugar contribute to tooth decay and may increase the risk of weight gain and obesity. Consumption of sugary foods may also reduce the consumption of foods containing the micronutrients needed for health.

Added sugar comes in many forms, including cane sugar, honey, corn syrup and other sweeteners. Added sugar is of course found in many pastries, soft drinks, jellies, candy, puddings, ice cream and other confections. Sugar is also often added to other processed foods that otherwise could be healthful:

|

granola; image from Stacy at Creative Commons

|

- Yogurt

- Peanut butter

- Granola and other whole-grain cereals

- Chocolate

- Fruit smoothies

- Tomato-based sauces

- Fat-free salad dressings

- Processed fruit, such as juices and applesauce

- Whole-grain crackers

Low-sugar or sugarless varieties of these foods are recommended.

Salt

Salt is a necessary nutrient for our bodies, but most people worldwide consume far more than needed—around twice the recommended maximum level of intake on average. Salt is the primary source of sodium worldwide, and increased consumption of sodium is associated with hypertension and increased risk of heart disease and stroke. Salt is added to food both during preparation and at the table. Foods particularly high in salt or sodium:

- Prepared meals and convenience foods

- Processed meats such as bacon, ham and salami

- Cheese

- Salty snack foods

- Instant noodles

- Soy sauce, fish sauce and other sauces

Bread and processed cereal products also contain salt, and, because they are consumed frequently in large amounts, can contribute to overconsumption of salt.

Malnutrition

Barriers to Obtaining Adequate Food

|

Malnutrition can come either from a lack of food or from a lack of the right kinds of food. Malnutrition comes in two main forms:

- Protein-energy malnutrition, a lack of protein and calories, is more lethal than other forms of malnutrition and is generally what is meant in references to world hunger. This form of malnutrition can be caused by an unhealthful restriction in protein and calories that can lead to death, wasting or nutritional edema. An unhealthful restriction in nutrients can also cause stunting in children. A 2016 report estimates that 250 million children (43 percent) younger than five years in low-income and middle-income countries are at risk of not reaching their developmental potential because of extreme poverty and stunting.

- Micronutrient deficiencies are specific to micronutrients, including those discussed above. Severe micronutrient deficiencies can lead to health conditions including scurvy (vitamin C deficiency), pellagra (niacin or tryptophan deficiency), beriberi (thiamine deficiency), goiter or cretinism/neonatal hypothyroidism (iodine deficiency) and xerophthalmia (vitamin A deficiency). Moderate deficiencies can cause impaired cognitive development, excess bleeding and impaired immune system function leading to disease susceptibility.

During the 2014-2016 period, globally one in nine people, most of whom were in developing countries, were estimated to suffer from chronic undernutrition.

Diet and the Microbiome

The human microbiome—the collection of all the microbes found in our body, including bacteria, parasites, fungi, yeast and viruses—is essential to our health. Research on the microbiome is still very new, and more research needs to be conducted to understand its health impacts. To date, evidence indicates that our individual microbiomes are influenced by what we eat. In fact, much of the variation of gut microbiomes between people is thought to be due to differences in diet.

Pesticides and the Human Microbiome

Evidence—conducted mostly with animals to date—suggests that pesticides may interact with the human microbiome. For example:

- Microorganisms in the gut of rodents appear to play a role in the metabolism of DDT into DDD.

- The rodent gut microbiome also metabolizes propachlor.

- Glyphosate, in widespread use globally, appears to inhibit growth of bacteria in the gut microbiome of horses and cattle.

- In poultry, the impact of this inhibition on growth varies by the strain of bacteria. Certain pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella are resistant to the effects of glyphosate, while bacteria that support healthy gut function (such as Lactobacillus) appear to be susceptible to adverse effects.

In humans, limited evidence shows that chronic exposure of the microbiome of the human gut to chlorpyrifos alters the array of bacteria, favoring the growth of caustic bacteria over healthier species. More research is needed to better understand how the gut microbiome interacts with these chemical exposures and what that means for human health. |

Many—perhaps most—of these microbes aid in digesting food and fighting illness. The human gut microbiome can be quickly altered by a change in diet, sometimes as fast as within three or four days. These differences can affect which genes are transcribed for the body's production of proteins, potentially impacting how our bodies process food or respond to disease.

Research has found that animal-based diets increase the abundance of bile-tolerant microbes while also decreasing the colonies that digest plant carbohydrates. In mice, these differences may account for the association that has been found between meat consumption and an increase in bacteria known to foster inflammatory bowel disease.

Antibiotics, Animal Microbiomes and Human Health

Antibiotic use in animal husbandry is known to alter the gut microbiome of livestock in profound ways, for example including increasing E. coli populations soon after administration. These findings raise concerns about the functional capacity of the microbiota and potential for enteric (intestinal) infections.

Antibiotic alterations of the gut microbiota increase susceptibility to certain bacterial pathogens and have also been linked to viral and fungal infections and even disease susceptibility in distal organs. It is unclear if this has implications for human health as consumers of these animal products, especially when combined with the concern of antibiotic resistance (see below).

|

Diet shortly after birth might influence the populations of gut microbes, with variation in the microbiome between formula-fed and breast-fed infants. Our microbiomes may also be influenced by an overprocessed food supply, potentially contributing to the obesity epidemic. Some researchers suspect the rise of chronic diseases—including arthritis, obesity, cardiovascular disease and inflammatory bowel diseases—might be related to an imbalance of good to bad bacteria in the gut microbiome. More information about the microbiome is on the Microbibiome page.

Breastfeeding

Contaminants in Breast Milk

One of the most unfortunate outcomes of our exposures to environmental pollutants is the contamination of our breast milk. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs), pesticides, heavy metals, flame retardants, dioxins and other contaminants have all been documented in human breast milk.

A 2008 review weighing the risks from such contaminants against the benefits of breast milk concluded that "the WHO, the US Surgeon General, and the American Academy of Pediatrics continue to recommend breastfeeding."

|

Health professionals around the globe recommend exclusively breastfeeding infants from birth to six months of age if possible. Breast milk provides all of the nutrients and fluids an infant needs to fully support health and growth. Containing more than just nutrients and immune protection, breast milk provides information about the environment that new babies are living in, shaping biological features and influencing the development of the immune system, stress response, metabolism and fat deposition, brain development, growth, blood pressure and reproductive systems. Other impacts on health:

- Breastfed infants are less likely to experience diarrhea, ear infections and respiratory infections.

- Breastfed babies have lower risks of necrotizing enterocolitis, infectious diseases and obesity.

- Adults who were breastfed as infants are less likely to be overweight or obese or to develop diabetes or heart disease or to have a stroke.

- Mothers who breastfeed have a lower risk of breast cancer.

Food Safety

Top Risk Factors for Foodborne Illness

- Food becomes too warm

- Food sitting too long

- Poor personal hygiene

- Infected food handlers

- Dirty food equipment

- Cross-contamination

- Inadequate cooking

- Chemicals from containers

- Unhealthy chemical additives

- Unsafe sources

|

Food safety involves illnesses that arise from eating contaminated food, including foodborne disease and infections. Many contaminants can be found in the foods we eat:

- Harmful microbial agents (bacteria, worms, fungi, viruses and toxins)

- Chemical hazards (marine and mushroom toxins, heavy metals, pesticides, preservatives and additives)

- Residues of medicines from food animals (antibiotics and hormones)

- Foreign objects (bones, shells, glass, metal, stones, plastic, soil, hair)

- Radioactive materials

- Materials used in packaging (plastics, BPA, PFCs, waxes)

- Other contaminants (insect and rodent debris, cleaning agents)

Food Quality Regulations

In the US, the Food and Drug Administration regulates and enforces food safety generally, while the Department of Agriculture regulates meat and poultry products specifically. Some important regulations of food production in the US.

|

Bacterial pathogens alone account for many foodborne illnesses, responsible for diseases such as salmonellosis, botulism, staph infections, listeriosis and E. coli poisoning. Viruses are responsible for diseases like norovirus, while prions (shards of viruses) can cause mad cow disease, which has caused illness in small numbers of people.

Food Packaging

Food contact materials (FCMs) are the objects that come into contact with food, and include packaging, containers, processing equipment and preparation equipment. Many of these materials are human-made, including plastics, rubber, paper and metal.

Some of these items—can coatings, the lamination in paper containers, and plastic bottles, trays and wraps—contain chemicals that can leach into the foods they contact. This contact can be a source of food contamination. Researchers have identified these concerns with FCMs:

|

image from Melinda at Creative Commons

|

- Acknowledged toxicants are used legally, such as asbestos in rubber products and formaldehyde in plastic bottles. Both these substances are known to cause cancer.

- Some materials contain endocrine disrupting chemicals, such as BPA, tributyltin, triclosan and phthalates. Health impacts from endocrine disruption include some types of cancer, reproductive harm, obestiy, and nervous system harm, including neurobehavioral disorders, Alzheimer's disease and psychiatric disturbance. Research on health impacts from specific chemicals is far from complete.

- More than 4000 chemical substances are known to be used as FCMs, with many unknown byproducts and breakdown compounds (metabolites).

Flame retardants are generally fat soluble, capable of leaching from food wrapping and packaging into fat-containing products such as butter and meat. A 2011 study on flame retardants in food wrapping paper found that alarmingly high levels of decaBDE had leached from wrappers into butter products intended for human consumption. Flame retardants have been connected to reproductive toxicity, cancer, impaired neurological development, endocrine disruption and immune disruption.

Genetically Modified Foods

Genetically modified foods are those in which DNA has been altered through unnatural processes. Although humans have been genetically modifying foods through selective breeding for as long as humans have been farming, new technologies enable gene transfers between organisms in ways that are highly unlikely from natural breeding. For example, a Bt gene that provides resistance to a beetle pest is physically conveyed from a bacterium into tomato plants. This gene bestows innate protection against pests to the tomatoes, potentially leading to fewer pesticides used on crops.

A goal of genetically engineering food sources is to increase the amount and quality of food while requiring less effort and reducing cost. GMO crops currently on the market have been developed for an increased level of resistance against plant diseases caused by insects or viruses or for increased tolerance towards herbicides.

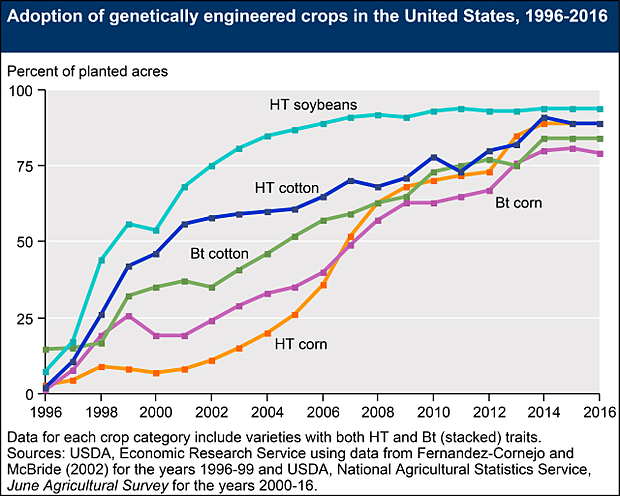

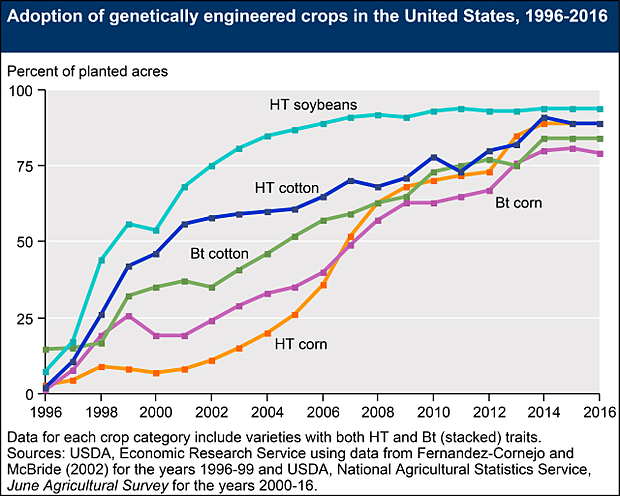

As of 2016, the United States Department of Agriculture reported that 92 percent of all US acres of corn, 94 percent of all acres of soybeans and 93 percent of all acres of cotton used genetically modified seeds.

Terms: HT, Herbicide-tolerant crops; Bt, Insect-resistant crops

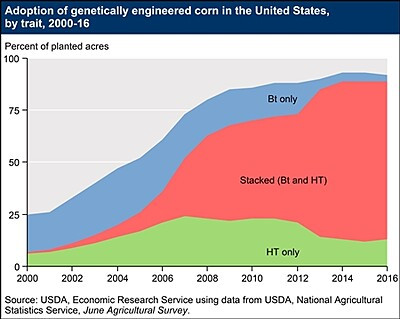

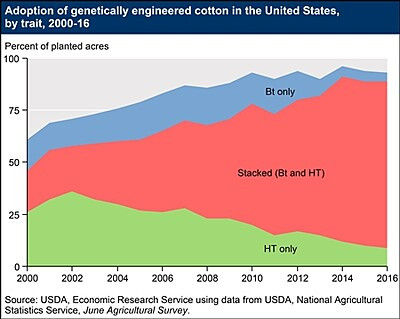

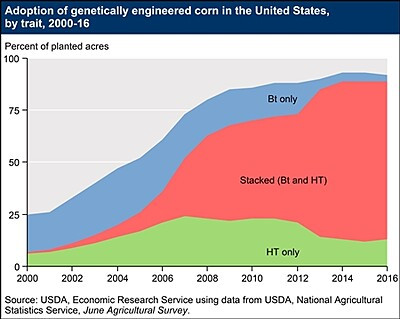

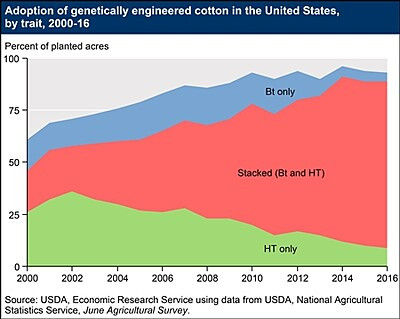

The substantial increases of GMO crops since the start of the twenty-first century have implications for pesticide use. In the graphs below, the green and red areas combined indicate use of HT (herbicide-tolerant) crops, whose benefit is derived when applying herbicides to crops, while the red and blue areas combined indicate use of Bt (insect-resistant) crops, which could indicate less use of insecticides:

|

|

|

Source: US Department of Agriculture; click images to zoom

|

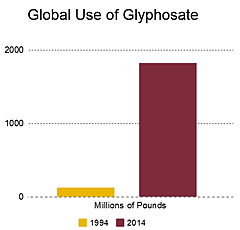

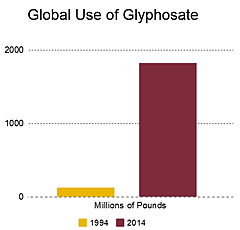

Glyphosate and GMOs

Glyphosate use has skyrocketed with the use of GMO crops. Globally, glyphosate use has risen almost 15-fold since genetically engineered, “Roundup Ready” glyphosate-tolerant crops were introduced in 1996. Two-thirds of the total volume of glyphosate applied in the US from 1974 to 2014 has been sprayed in just the last 10 years. The corresponding share globally is 72 percent. Worldwide use of glyphosate rose from a bit over 124 million pounds (over 56 million kilograms) in 1994 to more than 1.8 billion pounds (almost 826 million kilograms) in 2014.

|

The use of herbicide-tolerant crops has the potential to increase the use of herbicides dramatically, as seen with glyphosate at right. A 2016 analysis found that for both soybean and corn (maize), glyphosate-tolerant seed adopters used increasingly more herbicides relative to nonadopters, whereas adopters of insect-resistant corn used increasingly fewer insecticides from 1998 to 2011. The increase in herbicide use is a health concern if the herbicides used impact human health. The reduced use of insecticides should reduce exposures of farmworkers, their families and their communities to these toxic chemicals, and it may reduce residues of these chemicals in water. See our Pesticides page for more information about health effects of pesticides.

Concerns Related to GMOs

- Allergenicity, although to date no allergic effects have been found relative to GMO foods currently on the market

- Gene transfer from GMO foods to cells of the body or to bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract

- Outcrossing, migration of genes from GMO plants into conventional crops or related species in the wild

- Proliferation of genes into wild populations

- Susceptibility of non-target organisms, such as beneficial insects, birds and other wildlife to either host plant toxicity or to the increased use of pesticides that accompanies some GMO crops

- Loss of biodiversity

- Increased use of chemicals in agriculture and reliance on herbicides for herbicide-tolerant genetically modified crops (see above regarding glyphosate)

- Proprietary seed development whose plant does not produce seeds

- Food impact on the gut microbiome by herbicide reactivation in the gastrointestinal tract

|

The introduction of genetically engineered crops has been controversial. Some opponents claim that the health and environmental impacts of such foods are unknown and that the cross-breeding of GMOs with unmodified crops is uncontrollable. There is very little evidence to date that GMO foods themselves pose any health risk, but it's too soon to assess long-term impacts.

US Foods Currently Containing GMOs

- Corn-derived ingredients (oil, starch, corn syrup, alcohol)

- Soybean-derived ingredients (oil, soy flour, soy proteins, lecithin)

- Canola oil

- Sugar from sugar beets

- Papaya

- Squash

- Sweet corn

- Products from animals fed GMO grain (beef, chicken, pork, milk, yogurt, cheese, butter, eggs)

|

Because of varying genetic techniques for modifying plants, the safety and health impacts of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) cannot be assessed collectively but must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. The World Health Organization states that all available GMO products have passed safety assessment and are “not likely to present risk for human health”, nor have human health effects been observed where approved food are in commerce.

Future direction of GMOs:

- Improved resistance against disease and drought

- Crops with increased nutrient content

- Fish with enhanced growth characteristics

- Organisms that produce pharmaceuticals or vaccines

Agriculture and Aquaculture

Conventional Farming

Conventional farming, also known as industrial farming, has contributed enormously to the increase in food production over the last half century. Features of conventional farming:

|

image from Mercy for Animals Canada at Creative Commons

|

- Technological innovation

- Large-scale farms

- Single crop production

- Continuous growing

- Use of high-yield crops

- Extensive use of pesticides, fertilizers and external energy

- High labor efficiency

- Confined, concentrated livestock production

The Problem of Livestock Manure

Many farms in the US no longer grow their own feed and thus do not have a need to turn their manure into fertilizer. Large-scale industrial agricultural facilities—concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs—can produce enormous amounts of unused animal waste—more fecal waste than a city produces. Although sewage treatment plants are required for human waste, no such treatment facility exists for livestock waste.

Beef cattle in a feedlot; image from US Department of Agriculture at Creative Commons

Untreated manure can be applied to the ground, but at the risk of oversaturating the land with nitrogen, phosphorus and heavy metals. Manure can also contain pathogens such as E. coli, growth hormones, antibiotics and other chemicals and contaminants. Thus ground storage poses a hazard to water quality and a risk to human health (see the section on nitrates and water contamination below).

Manure can also be shipped off-site, held in ponds or treatment lagoons, or stored in underground pits. Ponds and lagoons are susceptible to overflow or breaching and spills during heavy rain. Even when operating as intended, lagoons can contaminate groundwater.

Animal feeding operations produce several types of air emissions, including gaseous and particulate substances. The most typical pollutants found in air surrounding CAFOs are ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, methane and particulate matter, all of which have varying human health risks. Emissions and odors from CAFOs can substantially impact the quality of life of surrounding communities. Rates of childhood asthma are increased in many neighborhoods surrounding CAFOs. A 2002 study found that occupational asthma, acute and chronic bronchitis and organic dust toxic syndrome can be as high as 30 percent in factory farm workers.

Manure emits methane and nitrous oxide, which are 23 and 300 times more potent as greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide, respectively. Globally, livestock operations are responsible for approximately 18 percent of greenhouse gas production and more than seven percent of US greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to climate change.

Many of the pathogens in livestock manure are concerning because they can cause severe diarrhea. Healthy people who are exposed to pathogens can generally recover quickly, but those who have weakened immune systems are at increased risk for severe illness or death. Vulnerable populations include infants and young children, pregnant women, the elderly and those who are immunosuppressed, HIV positive, or undergoing chemotherapy.

In sum, poor handling of excess manure can result in contaminated drinking water, ambient air pollutants and increased risk of disease.

|

The philosophy that supports conventional farming views nature as a competitor to be overcome. This perspective raises several concerns regarding the costs of conventional farming on the health of ecosystems:

- Decline in soil capacity and desertification

- Water pollutants and dead zones

- Water scarcity and the depletion of aquifers

- Pesticide impact on non-target species including pollinators

- Pest resistance

Food Choices and Climate Change

- Globally, 30 percent of human-created greenhouse gas emissions are from agricultural practices. In the US, the figure is 9 percent.

- Livestock production for meat, eggs and dairy products creates nitrogen and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Studies in the European Union demonstrate that cutting the consumption of livestock foods in half would reduce nitrogen and greenhouse gas emissions by up to 40 percent.

- Reducing meat, dairy and eggs in the diet would also reduce the risk for heart disease by reducing the intake of saturated fats.

- In a 2008 assessment, food production accounted for 83 percent of the average US household’s carbon footprint for food consumption, while 11 percent was attributed to food transportation.

- A dietary shift away from meat and livestock products may have more of an impact on climate change than buying locally produced food.

|

Specific concerns to human health from conventional farming include pesticide and nitrate contamination in food and water supplies and the use of antibiotics in animal production and the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Agriculture's Impact on Water Quality

Rain, snowmelt and irrigation water that isn't absorbed by soil or doesn't evaporate flows across farmlands, ultimately ending up as surface water—creeks, rivers, ponds, lakes, and oceans. This runoff picks up contaminants from soil and other surfaces it traverses and can include pesticides, animal waste, heavy metals, phosphorus and nitrates. This runoff pollution is the primary source of contamination in lakes and rivers. Water that collects in low areas and eventually percolates down into the soil can also contaminate groundwater.

Sewage Sludge and Health

Sewage sludge (also known as 'biosolids') is the semi-solid matter left over from municipal waste water treatment. Sewage sludge can contain pathogens such as E. coli, residues of pharmaceuticals, and potentially harmful levels of toxic metals and environmentally persistent chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins. These contaminants can remain in soil, increasing over time, and can be transferred to water and food.

Both storing sludge in open fields and spreading sludge near wells and surface water increase the risk that sewage sludge pathogens will be transmitted to workers, farmers and neighbors. Use of sewage sludge also increases heath risks from the elevation of heavy metals and other pollutants in the soils and foods and from the release of mercury into the atmosphere from spreading sludge.

|

Nitrogen-based fertilizers, as well as wastes from animals and humans, decompose within soil and water to form nitrates and nitrites. Globally, the increasing use of artificial fertilizers, the disposal of wastes (particularly from animal farming) and changes in land use are the main factors responsible for the progressive increase in nitrate levels in groundwater supplies since 1990.

Nitrates and Health

- Water runoff from land with excess nitrogen-based fertilizer can create algal blooms leading to “dead zones” such as that seen in the Gulf of Mexico.

- The primary route of human exposure to nitrates is through drinking water.

- Concentrations of nitrate in water under agricultural land can be up to 100 times higher than under land with natural vegetation.

- Communities living near agricultural fields—many using private wells—typically have higher levels of nitrate-contaminated drinking water.

- In addition to blue baby syndrome (methemoglobinemia), nitrates are associated with heart attacks and arrhythmias, cognitive impairment, stomach cancer and Raynaud's phenomenon.

- Ingestion of nitrates is “probably carcinogenic to humans” earning it a Group 2A IARC listing. See our Cancer page for more information on cancer classifications.

|

High levels of nitrates in the body, such as when a person becomes dehydrated, can impede oxygen availability in the blood, depriving cells of needed oxygen. Children under four months old are at highest risk from nitrate-related effects, including a potentially lethal condition known as blue baby syndrome. Pregnant women are also at increased risk.

In 2010, US researchers found that 64 percent of shallow monitoring wells in agricultural areas showed nitrate contamination “too high.”

1999 map from the US Geological Survey

Antibiotic Use in Agriculture

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when bacteria that cause disease in humans and animals become resistant to antibiotics. The use of antibiotics, especially in conventional farming, may be a significant contributor to antibiotic resistance globally.

Antibiotic use in US agriculture is on the rise, with an increase of 16 percent from 2009 to 2012. In contrast, the Netherlands, Europe's largest livestock producer, reduced the use of antibiotics for livestock by 50 percent during the same period. FDA data indicate that 80 percent of the 30 million pounds of antimicrobials sold in the US each year are given to animals.

|

Antimicrobial use in the US; click to zoom

|

97 percent of those antimicrobials for animals are sold without prescription, indicating that they are not necessarily for treatment of disease but may be for disease prevention and growth promotion. Intensive livestock production methods that crowd animals, deprive them of access to nature, divert them from the foods they evolved to eat and inhibit their natural social interactions necessitate antimicrobials to keep animals healthy and maintain productivity.

In addition to well-founded concerns about the increase of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria and the implications for treatment of human bacterial infections, concerns are mounting about effects of antibiotic residues in animal products on young children or on people with allergies or other health conditions. Antibiotic use, especially early in life, is known to impact weight gain in both humans and animals, for example. This effect may endure well into adulthood.

Sustainable Farming

Permaculture

The word permaculture, a combination of the words permanent and agriculture, refers to a system that relies on the natural ecosystem to grow or raise food in a way that doesn’t degrade the environment. By focusing on the symbiotic relationships of plants, animals, structures, landscapes and human activities, food production is more sustainable.

Key facts about permaculture techniques:

- Systems are maintained to minimize labor, energy and materials.

- Waste is recycled, minimizing pollution.

- Systems are diverse, increasing resilience and stability.

- Multiple facets of ecosystem are considered in the design, including slope and orientation of land, placement, function of each element, biological resources, energy recycling, natural selection, diversity and appropriate technology.

|

The long-term viability of our current (conventional) food production system is being questioned for many reasons. Since the mid 1990s attention has been growing to develop and implement sustainable agriculture—farming systems that can maintain “their productivity and usefulness to society indefinitely.” Sustainable farming must conserve resources and be socially supportive, commercially competitive and environmentally sound.

Commercial Composting

Large-scale composting facilities are a sustainable and environmentally friendly way to mitigate waste production and also reduce contributors to climate change. Large-scale composting facilities are a sustainable and environmentally friendly way to mitigate waste production and also reduce contributors to climate change.

image from Toxipedia; click to zoom

Benefits of composting:

- Soil with compost is more nutritious for plants and holds water better

- Soil with compost needs less water, fertilizer and pesticides

- Soil with compost has more microbes, making healthier soil and protecting plants from disease

- Adding compost reduces erosion

- Less waste goes to landfills

- Less methane is emitted from the decay of composted materials

- Adding compost increases the amount of carbon stored in soil

Compost may unfortunately include contaminants such as plastic, glass, and chemicals. See resources in the Dig Deeper section at right for information on regulating compost.

|

The 1990 US Farm Bill states that sustainable agriculture refers to “an integrated system of plant and animal production practices having a site-specific application” that will, over the long term:

- Satisfy human needs for food and fiber

- Enhance environmental quality

- Make the most efficient use of nonrenewable resources and on-farm resources and integrate, where appropriate, natural biological cycles and controls

- Sustain economic viability

- Enhance the quality of life for farmers and society

|

Cover crops sown between crop growing seasons reduce erosion, weeds and water runoff, and also improve soil quality when plowed under before planting crops; image from Chesapeake Bay Program at Creative Commons

|

Sustainable agriculture techniques currently employed by farmers to achieve the key goals of weed control, pest control, disease control, erosion control and high soil quality:

- Crop rotation

- Cover crops

- Soil enrichment

- Natural pest predators

- Biointensive integrated pest management

Aquaculture

Aquaculture—also known as fish or shellfish farming—is the breeding, rearing and harvesting of plants and animals in all types of water environments including ponds, rivers, lakes and oceans, and also human-made structures such as tanks, cages or raceways. The most common aquaculture foods include these:

|

image from Charlotte Wasteson at Creative Commons

|

Marine aquaculture:

- Oysters

- Clams

- Mussels

- Shrimp

- Salmon

|

Catfish being fed in a canal in Thailand. image from Bill Stilwell at Creative Commons

|

Freshwater aquaculture:

- Catfish

- Trout

- Tilapia

- Bass

As in agriculture, different methods of aquaculture have varying impacts on the environment and human health. Concerns raised about farmed fish:

- Transfer of disease and parasites both among confined, crowded animals and into wild populations

- Increased use of antibiotics and fungicides due to crowded, unsanitary conditions

- Introduction of dyes used to make farmed fish more attractive to consumers

- Introduction of foreign species into native populations through escapes

- Excessive pollution from fish excrement and uneaten feed, impacting neighboring populations in open water

- Higher levels of contaminants, such as PCBs, metals and pesticides; a 2016 analysis found that levels of most organic and many inorganic pollutants were higher in aquaculture products

- Lower levels of beneficial omega-3 fats; a 2016 analysis concluded that by replacing fishmeal and fish oil in farmed salmon diets with sustainable alternatives of terrestrial origin, terrestrial fatty acids have significantly increased alongside a decrease in certain omega-3 (EPA and DHA) levels

- Lower levels of protein in farmed fish, influenced by the feed source

Home Gardening

Producing food at home or as part of a neighborhood community has health benefits from many aspects:

- Increased time and activity in a natural environment, with positive impacts on both physical and mental health

- Access to fresh-picked food, which can be higher in some nutrients—such as vitamin C and perhaps B vitamins—than foods harvested several days earlier and shipped to a grocery store

- The ability to reduce use of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers

- Cost savings, especially compared to some organically grown commercial foods

- Opportunities for social interaction in community gardens

- The ability to recycle kitchen and yard waste into compost, reducing climate change impacts of sending these to a landfill

- Involving children in growing food may increase their enthusiasm for eating more healthful foods

Why Is Soil Contaminated?

Contamination depends on local geology and land use and can come from these sources:

- Deteriorating leaded paint on buildings

- Vehicle exhaust from leaded gasoline or diesel fuel

- Mining

- Coal-fired power plants

- Industry, such as smelters or refineries

- Businesses such as gas stations or dry cleaners

- Waste sites, such as landfills or recycling centers

- Building materials, such as treated lumber

- Past agricultural use

- Naturally occurring minerals in some soils

|

Regrettably, a few negative considerations regarding home gardening and health are noted. First, soil in some neighborhoods and communities can be contaminated with these and other pollutants:

Some of these pollutants (such as arsenic and PCBs), can contaminate food grown in affected soils. Other substances (such as lead and asbestos) are a concern due to possible inhalation while working in soil, from transferring contaminants to hands and then to food, and from carrying these toxicants into the home. Soil tests are recommended before growing foods if any of the contamination sources listed at right are known or suspected.

|

image from Kathleen Lupole at Creative Commons

|

Second, there are some risks involved in home canning foods. Food poisoning is possible from inadequate hygiene or food preparation. Foodborne botulism is often caused by eating improperly processed food, particularly homemade canned, preserved or fermented foods. Extra care and attention to detail can avoid both these problems.

Further information about many of these topics is available in the CHE Publications and the Dig Deeper sections in the right sidebar.

This page's content was created by Lorelei Walker, PhD, and , and last revised in November 2016.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.

*Header Image: image from ep_jhu at Creative Commons

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet: Fact sheet No. 394. May 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- World Health Organization. 5 keys to a healthy diet. Viewed October 26, 2016; World Health Organization. Healthy Diet: Fact sheet No. 394. May 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Choose Fish and Shellfish Wisely: Fish and Shellfish Advisories and Safe Eating Guidelines. November 1, 2016. Viewed November 1, 2016.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Choose Fish and Shellfish Wisely: Should I Be Concerned about Eating Fish and Shellfish? September 22, 2016. Viewed November 1, 2016.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA and EPA issue draft updated advice for fish consumption. June 10, 2014. Viewed November 1, 2016.

- Office of Water. Contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in fish: polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). US Environmental Protection Agency. September 2013. Viewed October 31, 2016.

- Office of Water. Contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in fish: pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs). US Environmental Protection Agency. September 2013. Viewed October 31, 2016.

- Office of Water. Contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in fish: pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs). US Environmental Protection Agency. September 2013. Viewed October 31, 2016.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. National Listing of Fish Advisories General Fact Sheet 2011. December 2013. Viewed November 1, 2016.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. 7 Things to Know about Omega-3 Fatty Acids. National Institutes of Health. September 24, 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet: Fact sheet No. 394. May 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- Smith-Spangler C et al. Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives?: a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012 Sep 4;157(5):348-66.

- Barański M et al. Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses. British Journal of Nutrition. 2014 Sep 14;112(5):794-811.

- Średnicka-Tober D et al. Composition differences between organic and conventional meat: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Nutrition. 2016 Mar 28;115(6):994-1011.

- World Health Organization. 5 keys to a healthy diet. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- Micronutrient Initiative, in partnership with the Flour Fortification Initiative, USAID, GAIN, WHO, The World Bank, and UNICEF. Investing in the Future: A United Call to Action on Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies. 2009. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International micronutrient malnutrition prevention and control (IMMPaCt). Micronutrient Facts. March 31, 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016; Wax E. Iron in diet. Medline Plus. February 2, 2015. Viewed October 27, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International micronutrient malnutrition prevention and control (IMMPaCt). Micronutrient Facts. March 31, 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016; Wax E. Iodine in diet. Medline Plus. February 2, 2015. Viewed October 27, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International micronutrient malnutrition prevention and control (IMMPaCt). Micronutrient Facts. March 31, 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- IRRI. The Project: About Golden Rice. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- PubChem. Beta-carotene. October 22, 2016. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- Wax E. Vitamin A. Medline Plus. February 2, 2015. Viewed October 27, 2016; Ehrlich SD. Beta-carotene. University of Maryland Medical Center. March 23, 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International micronutrient malnutrition prevention and control (IMMPaCt). Micronutrient Facts. March 31, 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016; Wax E. Zinc in diet. Medline Plus. February 2, 2015. Viewed October 27, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International micronutrient malnutrition prevention and control (IMMPaCt). Micronutrient Facts. March 31, 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016; Wax E. Folic acid in diet. Medline Plus. January 16, 2015. Viewed October 27, 2016.

- Wax E. Vitamin D. Medline Plus. February 2, 2015. Viewed October 27, 2016; Norval M et al. Vitamin D status and its consequences for health in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016 Oct 18;13(10). pii: E1019; Trummer C et al. Beneficial effects of UV-radiation: vitamin D and beyond. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016 Oct 19;13(10). pii: E1028.

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet: Fact sheet No. 394. May 2015. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- Frank L, Kavage S, Delvin A. Health and the built environment: a review. The Canadian Medical Association. 2012. Accessed September 30, 2016.

- Cashman KD, Kiely M, Seamans KM, Urbain P. Effect of ultraviolet light-exposed mushrooms on vitamin D status: liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry reanalysis of biobanked sera from a randomized controlled trial and a systematic review plus meta-analysis. Journal of Nutrition. 2016 Mar;146(3):565-75.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. 2015. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Salt reduction. June 2016. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- Hunger Notes. 2016 World Hunger and Poverty Facts and Statistics. World Hunger Education Service. Viewed October 27, 2016; American Nutrition Association. USDA defines food deserts. Nutrition Digest. 2015; 38(2). Viewed November 7, 2016.

- Hunger Notes. 2016 World Hunger and Poverty Facts and Statistics. World Hunger Education Service. Viewed October 27, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition. Viewed October 18, 2016; Black MM. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2016 Oct 3.pii:S0140-6736(16)31389-7.

- Mother and Child Nutrition. Malnutrition. March 6, 2016. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Micronutrient Initiative, in partnership with the Flour Fortification Initiative, USAID, GAIN, WHO, The World Bank, and UNICEF. Investing in the Future: A United Call to Action on Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies. 2009. Viewed November 2, 2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding. March 31, 2014. Viewed November 3, 2016 .

- Hunger Notes. 2016 World Hunger and Poverty Facts and Statistics. World Hunger Education Service. Viewed October 27, 2016.

- Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. 2016:2(16003).

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014(505); 559-563.

- Feltman R. The gut’s microbiome changes rapidly with diet. Scientific American. 2013. Viewed November 4, 2016.

- Looft T, Allen HK. Collateral effects of antibiotics on mammalian gut microbiomes. Gut Microbes. 2012:3(5);453-467.

- Morgan KK. Change your microbiome, change yourself. Genome.gov. Viewed November 4, 2016.

- Mead MN. Contaminants in human milk: weighing the risks against the benefits of breastfeeding. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008 Oct;116(10):A427-34; Adgent MA. Brominated flame retardants in breast milk and behavioral and cognitive development at 36 months. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2014 Jan;28(1):48–57; Lorber M, Phillips L. Infant exposure to dioxin-like compounds in breast milk. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002 Jun;110(6):A325–A332.

- Mead MN. Contaminants in human milk: weighing the risks against the benefits of breastfeeding. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008 Oct;116(10):A427-34.

- McInerny T. Breastfeeding, early brain development, and epigenetics – getting children off to their best start. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2014:9(7); Mead MN. Contaminants in human milk: weighing the risks against the benefits of breastfeeding. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008:116(10);A426-A434; World Health Organization. 5 keys to a healthy diet. Viewed October 26, 2016.

- Friis R. Essentials of Environmental Health, Second Edition. 2012. Jones & Bartlett Learning. Sudbury, MA.

- Friis R. Essentials of Environmental Health, Second Edition. 2012. Jones & Bartlett Learning. Sudbury, MA.

- Friis R. Essentials of Environmental Health, Second Edition. 2012. Jones & Bartlett Learning. Sudbury, MA.

- Friis R. Essentials of Environmental Health, Second Edition. 2012. Jones & Bartlett Learning. Sudbury, MA.

- Muncke J, Myers JP, Scheringer M, et al. Food packaging and migration of food contact materials: will epidemiologists rise to the neotoxic challenge? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2014:68(7); 592-594; European Food Safety Authority. Food Contact Materials. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- Muncke J, Myers JP, Scheringer M, et al. Food packaging and migration of food contact materials: will epidemiologists rise to the neotoxic challenge? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2014:68(7); 592-594.

- Schecter A, Smith S et al. Contamination of US butter with polybrominated diphenyl ethers from wrapping paper. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119(2):151-154.

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Flame retardants. National Institutes of Health. 2016. Viewed August 12, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Food safety: Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- Learn.Genetics. Genetically modified foods. University of Utah. Viewed October 28, 2016; World Health Organization. Food safety: Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Food safety: Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Recent Trends in GE Adoption. September 22, 2016. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Recent Trends in GE Adoption. September 22, 2016. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- Benbrook CM. Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environmental Science Europe. 2016;18(3).

- Perry ED, Ciliberto F, Hennessy DA, Moschini G. Genetically engineered crops and pesticide use in US maize and soybeans. Science Advances. 2016 Aug 31;2(8):e1600850.

- World Health Organization. Food safety: Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- Domingo JL. Safety assessment of GM plants: an updated review of the scientific literature. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2016 Sep;95:12-8.

- MacDonald RS. Safety of Genetically Modified Foods and Food Ingredients. Iowa State University Food Science and Human Nutrition. 2015. Viewed October 28 2016.

- World Health Organization. Food safety: Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Food safety: Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods. Viewed October 28, 2016.

- Gold MV. Sustainable agriculture: definitions and terms. United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library. August 2007. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- Hribar C. Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on Communities. National Association of Local Boards of Health. 2010. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Gold MV. Sustainable agriculture: definitions and terms. United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library. August 2007. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- Westhoek H, Lesschen JP, Rood T et al. Food choices, health and environment: effects of cutting Europe's meat and dairy intake. Global Environmental Change. 2014:26;196-205; Weber CL, Matthews HS. Food-miles and the relative climate impacts of food choices in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008:42(10);3508-3513; Smith P, Gregory PJ. Climate change and sustainable food production. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2012:72(1);21-28; US Environmental Protection Agency. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. October 6, 2016. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Gold MV. Sustainable agriculture: definitions and terms. United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library. August 2007. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- US National Library of Medicine. Tox Town: Agricultural Runoff. April 26, 2016. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Bioscience Resource Project. Sewage Sludge (Biosolids) — land application, health risks, and regulatory failure. Viewed November 3, 2016.

- Reilly M. The case against land application of sewage sludge pathogens. Canadian Journal of Infectioius Diseases. 2001 Jul-Aug;12(4):205–207.

- World Health Organization. Nitrate and nitrite in drinking-water. 2011. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Ward MH. Too much of a good thing? Nitrate from nitrogen fertilizers and cancer. Reviews on Environmental Health. 2009:24(4);359-363; Janssen S, Solomon G, Schettler T. Toxicant and Disease Database. Collaborative on Health and the Environment. 2011.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Nitrates/Nitrites Poisoning. 2013. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Nutrient pollution. The effects: human health. 2016. Viewed October 2016.

- US Geological Survey. The Quality of Our Nation's Waters: Nutrients and Pesticides: Nutrients. 1999. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Wallinga D. Meat and the microbiome. San Francisco Medicine.

- Wallinga D. Meat and the microbiome. San Francisco Medicine. 2014:87(9):25; Van Boeckel TP et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015 May 5;112(18):5649-54.

- Ianiro G, Tilg H, Gasbarrini A. Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: between good and evil. Gut. 2016 Aug 16. pii: gutjnl-2016-312297.

- Cruz S, Osentowski J. Permaculture: Sustainable Farming, Ranching, Living by Designing Ecosystems That Imitate Nature. US Department of Agriculture. Viewed November 2, 2016.

- Gold MV. Sustainable agriculture: definitions and terms. United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library. August 2007. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Composting in WARM. May 2012. Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Harkinson J. Are there toxins in your compost? Mother Jones. June 6, 2011. Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Gold MV. Sustainable agriculture: definitions and terms. United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library. August 2007. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- Union of Concerned Scientists. Sustainable Agriculture Techniques. Viewed October 29, 2016.

- NOAA Fisheries. What is aquaculture? Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Washington State Department of Health. Farmed Salmon vs. Wild Salmon. Viewed October 30, 2016; Center for Food Safety. Aquaculture: Human Health Risks. Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Rodríguez-Hernández Á et al. Comparative study of the intake of toxic persistent and semi persistent pollutants through the consumption of fish and seafood from two modes of production (wild-caught and farmed). Science of the Total Environment. 2016 Sep 23. pii: S0048-9697(16)32072-1.

- Sprague M, Dick JR, Tocher DR. Impact of sustainable feeds on omega-3 long-chain fatty acid levels in farmed Atlantic salmon, 2006-2015. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 22;6:21892.

- Craig S. Understanding Fish Nutrition, Feeds, and Feeding. Virginia Cooperative Extension. May 1, 2009. Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Rickman JC, Barrett DM, Bruhn CM. Review: nutritional comparison of fresh, frozen and canned fruits and vegetables. Part 1. Vitamins C and B and phenolic compounds. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2007;87:930-94.

- Kessler R. Urban gardening: managing the risks of contaminated soil. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2013 Dec;121(11-12):A326-A333; Rosen CJ. Lead in the home garden and urban soil environment. University of Minnesota Extension. Viewed November 3, 2016; North Carolina State Extension.

Minimizing Risks of Soil Contaminants in Urban Gardens. July 16, 2015. Viewed November 3, 2016. - World Health Organization. Botulism. August 2013. Viewed November 3, 2016.