Health is wholeness. It’s a concept that cannot apply solely to an individual since people and other beings have always lived within families, communities, ecosystems, and planetary-level conditions. The health of any part or the whole of this nested set of relationships is dependent on diverse, dynamic interactions among them all. Ecologic models of health attempt to portray this multi-level complexity.

Gene-environment interactions largely determine the health of people and populations, although as epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose pointed out years ago the causes of a disease in an individual person frequently differ from the determinants of the incidence of that disease in populations.1

Asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, various kinds of cancer, cognitive decline, dementia, reproductive disorders, neurodevelopmental problems and many others arise from multi-level, multifactorial circumstances. Asthma, for example, can be caused or triggered by combinations of toxic chemical exposures, environmental contaminants, inadequate nutrition and social stress, among others. But these so-called risk factors do not exist only at the individual level. Some, like neighborhood safety, air pollution, chemicals in consumer products, and food quality and availability are community—or even societal-level features influencing the health of everyone living there—albeit some more than others.

Variations in the manifestations of many disorders challenge the ways we classify diseases. For example, underlying changes in the lungs and immune systems of people with asthma and exposures that trigger their wheezing can be quite different from one person to another. And neurodevelopmental disorders are notorious for their overlapping mixtures of problems with attention, behavior, and cognitive and motor function.

Models represent how we think about, study and try to influence outcomes amidst this complexity. Implicit or explicit models fundamentally direct research design and decision-making. All models are simplifications—some more than others depending on where boundaries are set on what is included and what is left out.

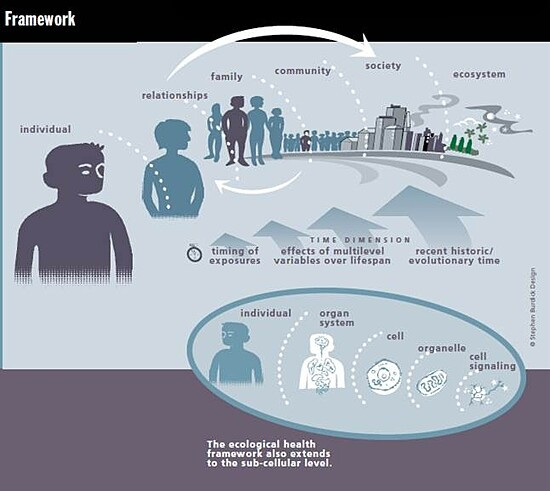

Ecologic models attempt to represent dynamic relationships within a nested hierarchy of person-family-community-ecosystem-society-planetary levels. They feature interactions and feedback loops. Health and disease patterns are largely determined by multi-level system conditions. An ecologic model should be valuable even to someone focused on only a portion of it.

CHE follows scientific research on any health concern linked to environmental contributors: everything besides hereditary factors that can impact health. We include social determinants of health under this umbrella because we recognize that poverty and other social stressors — along with chemical exposures and other factors — are all part of the environment in which we are born, grow and live. CHE recognizes that the chemical, biologic, physical, nutritional, built, natural and socioeconomic environments combine to create conditions that strongly influence the health of individuals and populations.

Sometimes there are good reasons for emphasizing particular determinants of health that stand out when there are opportunities to investigate and improve public health. For example, CHE has always had a strong interest in disseminating newly-emerging information about the impacts of environmental chemicals and contaminants on health because so many health care professionals, policy makers, and members of the general public have been unaware. CHE will continue to do that, recognizing that chemical exposures occur within an ecologic context that can make some people and populations more or less susceptible to their impacts.

Increasingly, many medical and public health challenges are seen as systems problems in need of systems solutions. Integrated, multi-dimensional, bundled interventions are most likely to be productive. Ecologic models embrace a multi-level array of the determinants of many common diseases and help in identifying strategic opportunities for their prevention and treatment.

This page's content was created by Ted Schettler, MD, MPH, with input from Elise Miller, MEd, and last revised in August 2016.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.