Public and environmental health policies are informed by a constellation of inputs from many sectors, including these:

- Scientific discoveries and skillful communication of those discoveries

- The influence of scientists, environmental advocates, industry, the media and others on the actions of policy makers

- Prioritization and economic investments by funders, governments and universities, and subsequent actions by governments, communities and individuals

Informing through Publications

Seminal books, reports and publications that change the dialogue for decision makers or create widespread awareness can also be pivotal, such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and these by CHE partners:

- Pesticides in the Diets of Infants and Children

- Generations at Risk: Reproductive Health and the Environment

- Our Stolen Future: Are We Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence, and Survival? A Scientific Detective Story (on endocrine disruptors)

- In Harm’s Way: Toxic Threats to Child Development

Consensus StatementsCHE's statements are listed on our Consensus Statements page. |

Convocations of esteemed scientists and related policy recommendations can also be influential, such as those convened by CHE:

- Vallombrosa Consensus Statement on Environmental Contaminants and Human Fertility Compromise

- Consensus Statement: Parkinson’s Disease and the Environment: Collaborative on Health and the Environment and Parkinson’s Action Network (CHE PAN) Conference 26–28 June 2007

A Systems Approach

Unfortunately, we still largely address public health and environmental challenges piecemeal, rarely consider the health of entire systems and neglect to develop a more integrated public health structure. A public health or environmental health crisis often spurs change, but much more than that is needed to shift entrenched scientific paradigms and develop a more comprehensive approach to sustainable development and pollution prevention.

One such health crisis occurred in 1854 in London that spawned the science of epidemiology as well as government investments in sewer improvements to protect water supplies.

The Broad Street Pump

![]()

|

A replica of the Broad Street pump in Soho, London, made famous after John Snow recommended removing its handle to stop a cholera outbreak in 1854; image from Peter MacInnis at Creative Commons |

Imagine it is the 1850s before it was known that cholera is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Imagine further you are in London, England, and your neighbors seem to be randomly contracting cholera and dying. Some thought it was caused by pollution or a noxious form of "bad air," but John Snow, a London physician, publicized his theory that cholera was transmitted by water in an 1849 essay, “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera.” Snow plotted the incidence of cholera on a map and noticed the increased incidence around a single source of water. As Snow stated, “On proceeding to the spot, I found that nearly all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the [Broad Street] pump.” Though his theory was not well accepted, the Broad Street pump handle was removed and the epidemic stopped. John Snow made this enormous contribution to public health and started the discipline of epidemiology, all before the exact cause and effect had been discovered.

Growing Body of Scientific Evidence Leading to Health-protective Policies: Examples

Advances in research and technology can also ultimately result in public policy and personal action changes:

- The ability to map the human genome

- More sophisticated research techniques and tools

- A growing body of evidence from academic and community-based researchers about the health and environmental impacts of substances, products and activities

Well-known examples of this slower process include the cases of tobacco, lead and mercury. Accumulating data leading to widespread knowledge about their harmful health effects coupled with courageous leadership of scientists and health professionals has led to laws and regulations designed to minimize exposures to toxic substances and protect human health.

|

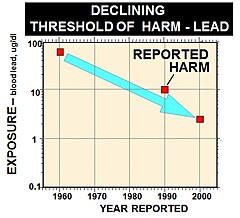

Exposures expressed in micrograms/deciliter (blood lead); graphic from Physicians for Social Responsibility;1 click to zoom |

Example: Lead

The public health impacts of lead are now are well documented, but that was not always the case. The understanding of lead has advanced over the period of a full century, during which time the recognized “toxic threshold,” (the lowest exposure thought to be harmful), has relentlessly declined. Today, most agree that there is no safe level of exposure.

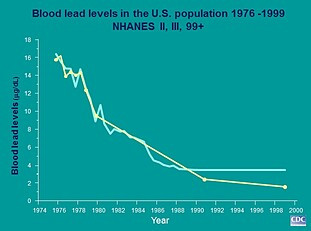

As lead was removed from products including gasoline and paint, children’s blood lead levels declined corresponding to the public health interventions.

Declining gasoline lead levels in blue and the corresponding decline in children's average blood lead levels in yellow; graphic from Physicians for Social Responsibility In Harm's Way;2 click to zoom

Unfortunately, as we have seen from the drinking water crises in Flint, Michigan, and other cities, we still have a serious public health problem with lead in water and from paint in housing, affecting primarily children and others who live in lower-income urban communities.

Example: Dioxins

|

"Dioxin" here is defined as the totality of 7 dioxins and 10 furans. "TEQ" denotes "toxic equivalent," a quantitative measure of the combined toxicity of a mixture of dioxin-like chemicals. Source: Toxipedia with data from US EPA;3 click to zoom |

Dioxin is a good example of how regulations have helped reduce environmental emissions in the US. Overall, industrial, municipal and transportation dioxin emissions have declined dramatically as a result of dioxin regulation, whereas emissions from backyard barrel burning of rubbish and residential wood burning have remained essentially constant since 1987.

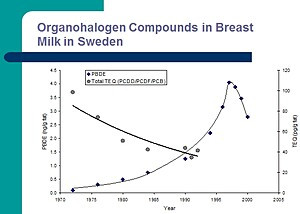

Example: PBDEs

Polybrominated diphenylethers (PBDEs) are a family of flame retardants used in large numbers of consumer products including clothing, upholstery and electronic equipment like televisions and computers. The graphic below shows trends of breast milk contamination with PCBs/dioxin and PBDEs in Sweden over a 30-year period. While PCB/dioxin levels slowly dropped, PBDE levels rose at a rapid rate until the late 1990s when Sweden enacted regulatory controls, including manufacturing restrictions on PBDEs. This regulatory action probably explains the decline in breast milk levels beginning at that time.

Terms: PCB, polychlorinated biphenyl; PCDD, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin; PCDF, polychlorinated dibenzofuran; PBDE, polybromonated diphenylether; TEQ, toxic equivalent); graphic from Physicians for Social Responsibility4 click to zoom

Example: Mercury

|

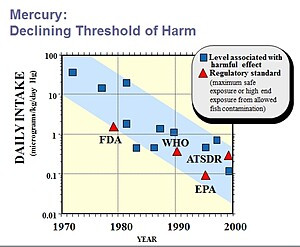

Exposures expressed in micrograms/deciliter (blood lead); graphic from Physicians for Social Responsibility;5 click to zoom |

The apparent toxic threshold for mercury has declined over three decades with advancing knowledge. This graph illustrates that decline and also shows that different regulatory agencies have set different thresholds.

Example: Nutrition and Exercise

In addition to toxicants, we have seen how government, community, funder and health care emphasis on healthier foods and the value of exercise have driven changes in everything from providing healthier school lunches to soda taxes, with both incentives and disincentives reflecting competing world views.

How Are Environmental Protection Laws and Regulations Influenced?

|

image from NASA |

Many major laws and regulations to protect the environment have been enacted following environmental health tragedies, chemical accidents, strategic activism, revelations of scientific research and even transformative events that have enabled people to see the interdependence of life and the fragility of our blue planet. They are shaped by scientific evidence, political and economic priorities.

Historical lessons can offer hope for how we can improve our multiple environments, provide cautionary tales about the dangers of ignoring troubling signs of environmental hazards, and serve to underscore the vital role of regulatory and policy agencies, the power of the people and the value of ongoing vigilance.

A few examples of historic environmental protections accidents, incidents and actions in the US, with some details following the table:

| Year | Incident or Action |

| 1945 | World War II nerve gas research leads to the postwar explosion of agricultural pesticides into the commercial marketplace. |

| 1947 | The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) is passed, prohibiting the sale of any pesticide shown to cause unreasonable, adverse effects to the environment during normal application. |

| 1962 | Biologist Rachel Carson publishes Silent Spring, heralding the dangers of pesticides including DDT. |

| 1969 |

Ohio’s Cuyahoga River catches fire. An oil rig blows out off the coast of California. Apollo astronauts set foot on the moon and send from space the first photographs of “a wondrous ball of blue and green, rich in life.” |

| 1970 |

First Earth Day: more than 20 million Americans rally to celebrate the environment and protest pollution. The federal Environmental Protection Agency is established. The Occupational Safety and Health Act is passed. The Clean Air Act is passed. |

| 1972 |

The Clean Water Act is passed. The Consumer Product Safety Act is passed. DDT production is banned in the US. |

| 1974 | The Safe Drinking Water Act is passed. |

| 1976 | The Toxic Substances Control Act is passed. |

| 1978 | Love Canal in Niagara Falls, New York, is the nation’s first declared federal emergency for a human-made environmental disaster as a result of more than ten years of toxic dumping. |

| 1980 | The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, commonly known as “Superfund”, is passed. |

| 1984 | An explosion of the gas methyl isocyanate in Bhopal, India, at a Union Carbide plant kills thousands and injures hundreds of thousands. |

| 1986 | The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act is passed which includes the landmark Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act that also established the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI). |

| 2016 | It takes 40 years of pressure from public health advocates and scientists to enact reforms to TSCA, known as the Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act. |

Highlights of How Major US Environmental Health Laws and Regulations Work

This section is drawn in part from Generations at Risk: Reproductive Health and the Environment.6

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the authority and responsibility to regulate toxic chemicals under the following:

- Clean Air Act (CAA) for toxic air pollutants

- Clean Water Act (CWA) for toxic water contaminants

- Resource Conservation Recovery Act (RCRA) for toxic wastes deposited in or on the ground

- Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) which was amended by the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) for pesticides

- Toxics Substances Control Act (TSCA) for toxic chemicals generally.

Sometimes two or more of the laws overlap, or one or more agencies share regulatory authority. For example, both the EPA and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulate worker exposure to harmful chemicals.

Manufacturers of pesticides and pharmaceuticals are required to test the effectiveness and safety of their products prior to their review for registration purposes, a relatively precautionary approach. Unfortunately, for pesticides, the testing is incomplete and not fully health-protective, yet the legislative intent is that the safety of all newly proposed pesticide products be evaluated prior to marketing.

Most other of the more than 80,000 chemicals used by industry in the US have not historically undergone similar scrutiny under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which did not require manufacturers to prove the safety of chemicals before introducing them to the marketplace. The first reform to the 1976 TSCA law was finally enacted in 2016, the Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act. It provides the EPA important new powers to require chemical testing and to take action to restrict priority chemicals and more authority for chemical testing. The public and environmental health communities wait to see if the new provisions will be effective.

|

image from Todd Lappin at Creative Commons |

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA, or Superfund) provides a Federal "Superfund" to clean up uncontrolled or abandoned hazardous-waste sites as well as accidents, spills and other emergency releases of pollutants and contaminants into the environment. Through CERCLA, EPA was given power to seek out those parties responsible for any release and assure their cooperation in the cleanup and when possible to recover costs from responsible parties (“polluter pays”). CERCLA was originally funded by a tax on the chemical and petroleum industries, but in 2002, the Bush administration shifted the tax burden from industry to the general public. As a result, the fund was depleted by 2004, slowing cleanup at Superfund sites and leaving taxpayers responsible for future cleanups when polluters cannot be identified or are unable to pay.

The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA, or SARA Title III), an amendment to the hazardous waste site Superfund law, requires the owners and operators of large manufacturing facilities to report to the EPA and state regulatory agencies their environmental releases (to land, air and water) and off-site transfers of certain toxic chemicals on an annual basis, and also to the public in a computerized “Toxics Release Inventory” (TRI), the first publicly accessible, online computer database ever mandated by federal law.

The Food and Drug Administration is responsible for protecting public health:

- Ensuring the safety, efficacy and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products and medical devices

- Ensuring the safety of our nation's food supply, cosmetics and products that emit radiation

- Responsibility for regulating the manufacturing, marketing and distribution of tobacco products.

Although it was not known by its present name until 1930, FDA’s modern regulatory functions began with the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act. Legislation authorizing FDA's responsibility for regulating ingredients in cosmetics is weak and ineffective, leaving the industry essentially in the position of regulating itself. New legislation to correct this is pending before Congress.

|

image from Alan at Creative Commons |

The California Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act (Proposition 65) was passed as a ballot referendum in 1986. This law protects the state's drinking water sources from being contaminated with chemicals known to cause cancer, birth defects or other reproductive harm, and requires businesses to use warning labels to inform Californians about exposures to such chemicals from consumer products. Proposition 65 requires the state to maintain and update a list of chemicals known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.

See more about using science to inform change in the list of CHE publications and Dig Deeper resources in the right sidebar.

This page's content was created by Maria Valenti and last revised in October 2016.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.